Rishi Sunak may be measured on terms set by a former PM

After all the drama and derision of the UK’s political shenanigans over the last few months, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak may well be measured on terms determined by a former Prime Minister. The new Prime Minister will, proclaimed Theresa May, provide the sort of “calm, competent, pragmatic leadership our country needs at this deeply challenging time.”

In his first statement on winning the Conservative MPs’ ballot following the withdrawal of first Boris Johnson and then Penny Mordaunt, Sunak had set out his priorities: to “fix” the economy, bring his party together, to stand and “deliver.”

The first two priorities may be evaluated through quantifiable data; the last two priorities may be evaluated in terms of how persuasive Sunak is. Each priority must consider multiple realities—financial, partisan, community-based, and multinational—but none will be easy to overcome.

Sunak must move quickly but carefully to calm the markets and reassure allies that Britain has woken up and grown aware of the serious political consequences if it all goes wrong. He is increasingly seen as someone capable of stabilising the UK’s fragile economy, the tenuous link between interest rates and investment notwithstanding. When it comes to economic credibility he is regarded as the acceptable face of what it takes to be party leader (something akin to Tony’s Blair’s persona in 1997) and what it takes to be a Prime Minister internationally.

Prime Minister Sunak may yet be seen as disingenuous. To have one’s plans cause trouble for others is to be hoist by one’s own petard. Indeed, he would be well counselled to steer clear of grandiloquent flourishes, surprise announcements, ideas about “disruptive innovators,” and diatribes against consumerism. These were characteristic of the constant tale of woe told by his two direct predecessors: the breathless Liz Truss, and Boris, with his Johnsonian flowery speeches.

The burden of Sunak’s first one hundred days in office is the polar opposite of what is routinely envisioned for global leaders. Even a week is a long time in politics, explained the Liberal politician Joseph Chamberlain in 1886. “In politics, there is no use in looking beyond the next fortnight.” Considerable change can happen in a short window.

Is Britain reverting to the tempestuous roller-coaster 70s? It is winter, and discontent is ever present.

There will be hard times for Prime Minister Sunak in the road ahead if he is to restore the United Kingdom’s integrity, its foreign policy, and its Anglo-Saxon sense of pragmatism.The sheer range of political issues confronting Rishi Sunak, as the United Kingdom’s new Prime Minister, involve looking again at energy costs, climate change, the war in Ukraine, as well as relations with the People’s Republic of China and the Indo-Pacific region. Africa, the United States, worldwide health concerns, international law and security will be next on the agenda. New science and technology, trade, and the universal economic crisis are also to come: these challenges are part and parcel of being a global leader.

The cost of energy continues to be a serious concern for households and businesses in the UK and, given the cost of government intervention, it will eliminate any residual public funding. The policy currently in place, capping the unit price for six months, increases affordability but will offer only a token relief package for this winter. Crucially the new Conservative government needs to look again at what happens to bills in the spring and following winter which, from a perspective of gas supplies, may well be worse than this one. The EU has reacted with a sense of concerted resolve, proposing new legislative packages to diversify supply, quicken the deployment of renewable energy, make changes to markets, and bring in energy saving measures. While these are unlikely to be enough in themselves they could bridge a gap and become a gauge for UK domestic policy to measured.

How can we avoid returning to the 1970s? In October, the UK lost 417,000 working days due to labour strikes, the highest number in more than 10 years. The statistics from November and December are not going to make for inspiring reading either.

Is Britain reverting to the tempestuous roller-coaster 70s? Double-digit inflation is powered in part by energy prices bolting out of the blue, with interest rate hikes and strikes all around. It is winter, and discontent is ever present. The 70s revisited redux… Yet is it really? When Harold Wilson’s minority government took office on 4 March 1974, its focus was to try to regulate wage increases because of inflation. What seems to have happened today is that working arrangements—the trade unions, the TUC, which created a social contract—would moderate wage increases to 3% or 4%, in return for the government providing extra care for social causes. One might expect, however, to resort to ACAS—the experts mediating between disputing parties—according to Professor Alex Bryson, of University College London. (Last year there were 500-600 employer-employee disputes!) Like today, the 1970s saw double-digit inflation, but there were important differences.

Sooner or later, someone needs to tell Prime Minister Rishi Sunak that he’ll have to increase public spending in the end, or the quality of public services will inevitably deteriorate. The Guardian and the Daily Express have already implored the PM to seek an independent pay review in light of the nurses’ strike. (Although The Telegraph pointed out the risks it implies for inflation throughout the public sector.) “Sit down and sort this out” was the Express’ headline. The Times sees the ambulance services as in most danger, bracing itself for a 40% increase in hospital admissions: “Ambulance strikes set to pose the biggest threat of all.”

For over a decade nurses—the ‘nation’s angels’—have seen their salaries decline in real terms. And, like rail workers, the Border Force, baggage handlers, and teachers, they have voted to walk out. The nurses’ cause, spearheaded by Dame Elizabeth Anionwu—the first sickle cell and thalassaemia specialist nurse—is supported by over 60% of the electorate. What does she say about the political rhetoric concerning migration, while personnel shortages grip many professions and multiple industries? “You can’t have it both ways.” Happily ever after doesn’t do it. She’s only the third nurse to be awarded the Order of Merit, and “simply the best.”

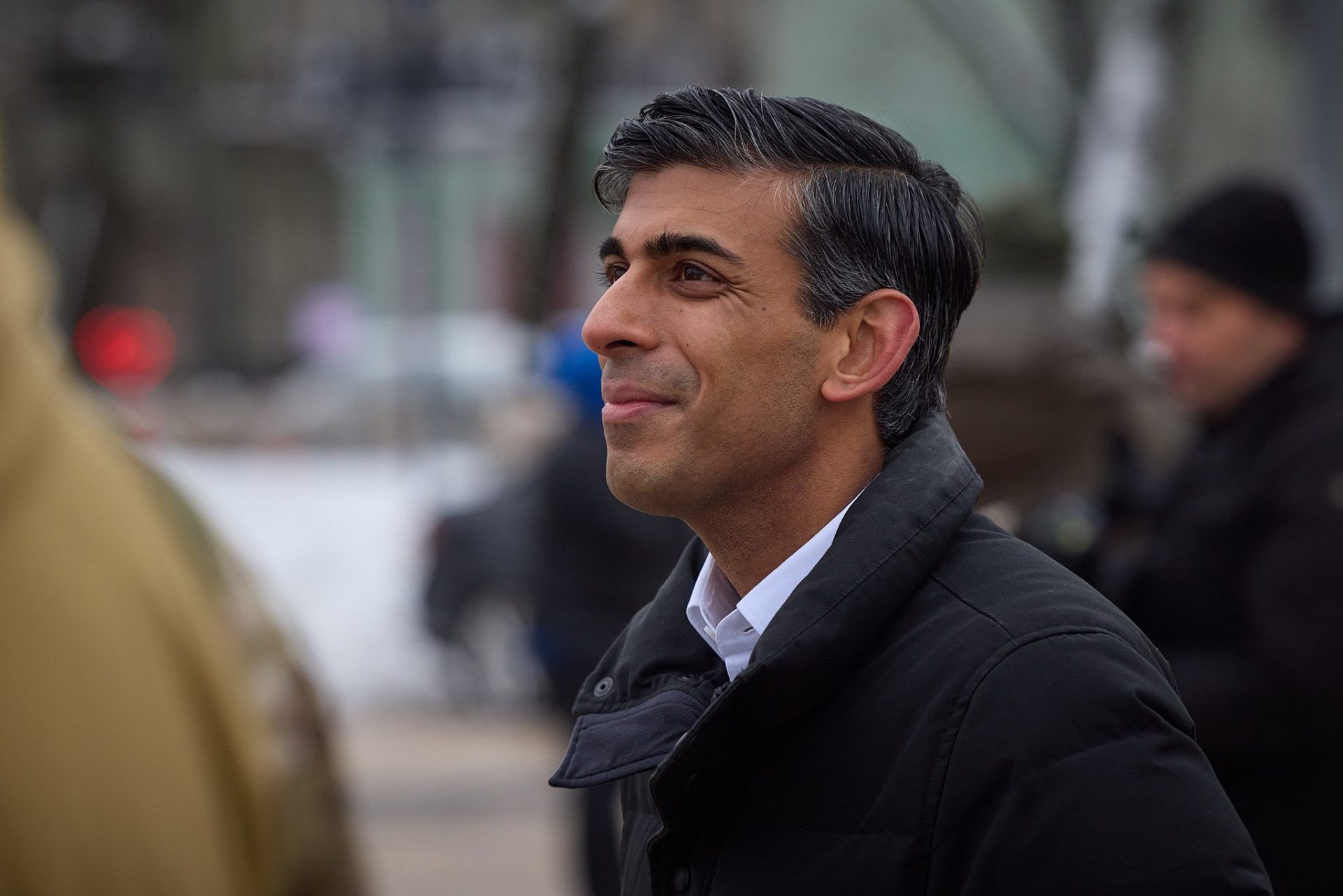

Photo Credits: British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak meeting with President Volodymyr Zelenskyy in Ukraine, 19 November 2022 (Wikimedia Commons, CCO Public Domain).