Bombs and Books: Franco-Algerian Collaboration and the Reconstruction of the Bibliothèque Nationale d’Algérie

Share the post "Bombs and Books: Franco-Algerian Collaboration and the Reconstruction of the Bibliothèque Nationale d’Algérie"

Around midday on June 7, 1962, residents of Algeria’s capital city watched smoke rise above the buildings in Alger-Centre, near the port. Nearly three months after the signing of a ceasefire between France and Algeria in March 1962 that marked the end of the Algerian War for Independence, attacks by the para-military group the Organisation Armée Secrete (OAS) continued. That day, the OAS placed three phosphorous bombs in the Université d’Alger’s main library building on the rue Michelet.[i] As firefighters rushed to the scene, onlookers watched flames and black smoke pouring out of the library’s windows.

The Bibliothèque universitaire d’Alger (BU) was of one of the continent’s oldest and richest libraries, comprising more than 600,000 monographs as well as manuscripts in Arabic and Latin. Once the fire was finally brought under control, the damage was substantial. Reports differ, but likely more than 400,00 volumes were lost to the flames.[ii] According to Le Monde, damages to the books and buildings were valued at over 70 million NF, not to mention the destruction of “des manuscrits arabes inédits et de precieux ouvrages aujourd’hui épuisés.”[iii]

2022 marked the sixtieth anniversary of the end of the Algerian War for Independence—and of these attacks on the university library. Though relatively little scholarly research exists on this topic, the destruction of one of the country’s most recognizable intellectual sites continues to loom large for Algerians. It is a symbol of the deep wounds inflicted upon the nation by French colonialism and the war (which led to the death at least 250,000 people). It also symbolizes, however, how Algerians reclaimed their heritage, banded together, and used new and old alliances to rebuild and reimagine their nation after independence.

Early June 1962 was relatively quiet, all things considered. For five days, the OAS committed no attacks, despite the fact that many European-descended Algerians were dissatisfied with Franco-Algerian negotiations continuing over the nation’s future. These new attacks were the result of infighting between OAS leaders, one marked event in a tumultuous summer before Algeria officially became independent.[iv] Following negotiations with French leadership, Jean-Jacques Susini, one of the co-founders of the right-wing paramilitary organization, declared that they should maintain the partial ceasefire. Other leaders, however, were dissatisfied with this plan. Jean-Claude Perez denounced Susini’s decision, stating in a “emission pirate” that the OAS had been “sabotaged by the Gaullist powers” which had failed to protect the interests of Europeans in Algeria. The broadcast declared, after five days without attacks, that the “OAS is reclaiming its freedom starting this evening,” asking their commandos to “restart their operations aimed, above all, at economic targets.”[v] The OAS members responsible for destruction that followed were never identified or charged.

The OAS’s choice of target, seemingly made with limited leader oversight, was telling. On the same day as the bombing of the Bibliothèque Universitaire, other explosions were set at the Université d’Alger’s laboratories and two nearby amphitheaters. In the early hours of June 8th, as local cadres worked to put out the flames from these attacks, five other sites in Algiers were targeted: the post office and mayor’s office in El Biar, two colleges in the center city, a wing of the police prefecture, and, finally, the Palais d’Ete.[vi] As French journalist Yves Courrière later recounted, these were culturally valuable rather than economically important. Attacking them was a way to claim ownership over the very knowledge the French had (supposedly) brought to Algeria: “We were certainly not going to leave them ‘our’ culture and ‘our’ science!”[vii]

Algerians felt the symbolic power of this attack. If every OAS bomb had an impact, wreaking financial damage and rending the nascent government less stable, the bombing of the university library was especially heinous. Mahmoud Agha Bouayed, head of the Bibliothèque Nationale d’Algerie (BN), denounced the bombing vociferously.[viii] The BU’s destruction, he explained in October 1962, “will stay in men’s memory as one of the most odious crimes against human knowledge.”[ix] It was an attempt to deny Algerians the right to participate in the world of educated, elite Europeans—though, as Frantz Fanon famously explained, many Algerians may not have even wanted to join this cadre of colonial elites.[x]

Destroying libraries or sites of knowledge was not uncommon throughout the colonial conquest of Algeria and the struggle for its liberation. During the 1837 conquest of Constantine, for instance, the French Army pillaged all but a few manuscripts from the city’s collections. In fact, the BU contained thousands of manuscripts looted from by the French from Constantine, Mascara, Medea, and Blida.[xi] Throughout the eight-year war for Algerian independence, libraries and other sites of learning or culture were targeted by the OAS and French military. In addition to the June 1962 bombing of the BU and other university buildings, the French Army or paramilitary forces bombed the Bibliothèque municipal d’Alger and pillaged libraries housed in lycées and hospitals.

The OAS bombing of the BU should be seen as part of a longer campaign against Algerian culture and history. The destruction of the library represented more than an economic loss. Instead, it was a way for the OAS to claim knowledge itself, denying Algerians access to resources deemed to “belong” to Europeans. These attacks racialized and nationalized knowledge and knowledge-production, seeing access to “Franco-European” resources as a violation of colonial epistemic hierarchies. As historian Abdesettar Athmani argues, the fire was far from being an outlier in the trajectory of Algeria’s colonial past, as historian Abdesettar Athmani argued, “this fire [traduit egalement] to what the French colonial regime was doing to close the doors to knowledge to the Algerian people.”[xii] Just as non-European Algerians were denied education and prevented from accessing or participating in French cultural production, so did the bombing of the library represent a denial of access to the supposed positive values of French civilization imposed through colonialism. If more physically destructive, it resembles a similar claiming of knowledge as the French reclaiming of archival material, many still held by the Archives nationales d’outre-mer in Aix-en-Provence.

After achieving independence in 1962, Algerian leaders could respond to this epistemic violence through the structures of the state. Reconstructing the university library’s collections became a central priority of the new Ministry of Education. On October 31, 1962, Bouayed announced the “creation of a committee for the reconstitution of the university library.”[xiii] The Bureau du Comité international pour la reconstitution de la Bibliothèque universitaire d’Alger (CIRBUA) was officially created on December 19th, 1962 comprised of seven French and Algerian administrative members, led by Bouayed.[xiv]Together, they were tasked with gathering financial and material support to rebuild the library’s collections. As Bouayed later wrote, CIRBUA’s goal was to lead a struggle “for culture” which would “bring about a profound victory: one of the forces of the Spirit over obscurantisme.”[xv]

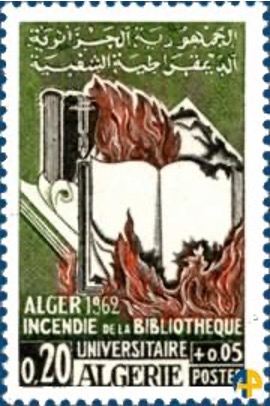

Rebuilding the BU’s collections took the better part of the next decade. CIRBUA drew support from anticolonial sympathizers in France, Europe, and across the African continent. In June 1965, 500,000 copies of a commemorative stamp depicting the fire were printed to memorialize the “scorched earth” politics of the French in Algeria and gather funds from everyday Algerians.[xvi] Similarly, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Syria, and Saudi Arabia printed commemorative stamps in 1965 featuring “a burned book, a charred library, [or] tools to put out fires” in honor of the bombing.[xvii] These international stamps were intended to raise funds for CIRBUA and the effort to rebuild the BU’s collections. Such cultural projects, especially insofar as they emphasized Arabic as Algeria’s natural language, were an opportunity for new post-colonial allies to contribute to the revolutionary state.

Meanwhile, the solidarity networks that had facilitated underground publishing between 1954 and 1962 were once again mobilized to support the library’s reconstitution. Bouayed reached out personally to various left-wing intellectuals and academics to see if they could help with donations “in books as well as in kind.”[xviii] He wrote personal letters to Daniel Guerin, Francois Maspero, and various others, asking them to send copies of their own books or any financial contributions to the library.[xix] Guerin sent a dozen books. Maspero sent along relevant texts on the Algerian War from his own publishing house and wrote to Italian publisher Giovanni Pirelli to see if Pirelli could do the same.[xx] Seeing the value in building collections in Algiers, the poet and CIRBUA member Jean Sénac even donated his archival funds to the national library system in 1972.[xxi]

Many French militants who promoted Algerian independence saw the library as an opportunity to support the new country. In 1964, the Association France-Algérie, then led by Edmond Michelet, asserted the importance of healing the wounds of the war, including the lasting legacy of the university library fire. “Erasing this memory is the primary task of partisans of franco-Algerian friendship. The new library of the Université d’Alger will therefore become the best gage of future relations between the two peoples.”[xxii]

As the BU was slowly rebuilt, the Bibliothèque Nationale d’Algérie (BNA)(which recovered the BU’s surviving volumes) benefitted from the state investment in educational infrastructure. Mahmoud Bouayed, also president of the BNA, celebrated the fact that the library system could “satisfy the thirst for culture of all national residents, from the savant in their laboratory… to the worker isolated in… his workshop.” The library, he continued “played a primary role” in promoting “mass education and the formation of a socialist consciousness, a revolutionary consciousness” amongst all Algerians.[xxiii] In an effort to make the collections accessible, the Bibliothèque Nationale even created in 1963 a “bibliobus” that traveled “the roads of Algeria to bring this spiritual bread to all Algerians, no matter where they are.”[xxiv] According to Bouayed, this effort surpassed their greatest hopes. Wherever the bibliobus went, “the whole village came out.”[xxv] After significant efforts by the government to collect funds and support, by 1965, the National Library contained more than 600,000 volumes, making it, according to Alger Ce Soir, “the first in Africa and one of the most modern in the world.”[xxvi]

After fifty years of of Algeria’s independence, the bombing of the university library continues to loom large for many Algerians. The Algerian National Library hosted an exhibition in 2022 that featured books partially rescued from the fire as well as images, press clippings, and documents commemorating the event.[xxvii] A conference organized by the maison de la Culture Ali Zaâmoum in Bouira to commemorate the event in May 2022 featured scholars and participants who underscored its impact. Abdesettar Athmani of the University of Béjaïa, borrowed Mahmoud Bouayed’s imagery from decades before. He explained that the bombing and subsequent fire was an “odious crime against knowledge” and that, in targeting this institution, “the OAS aimed to deprive Algerians of knowledge and of history” on the eve of their nation’s official independence.[xxviii] Another historian, Mohamed Lahcen Zghidi, noted that the burning of the library was one of the most important culture crimes committed by the French in Algeria.[xxix] Today, the Algerian government recognizes June 7th as “National Book and Library Day.”

After fifty years of of Algeria’s independence, the bombing of the university library continues to loom large for many Algerians. The Algerian National Library hosted an exhibition in 2022 that featured books partially rescued from the fire as well as images, press clippings, and documents commemorating the event.[xxvii] A conference organized by the maison de la Culture Ali Zaâmoum in Bouira to commemorate the event in May 2022 featured scholars and participants who underscored its impact. Abdesettar Athmani of the University of Béjaïa, borrowed Mahmoud Bouayed’s imagery from decades before. He explained that the bombing and subsequent fire was an “odious crime against knowledge” and that, in targeting this institution, “the OAS aimed to deprive Algerians of knowledge and of history” on the eve of their nation’s official independence.[xxviii] Another historian, Mohamed Lahcen Zghidi, noted that the burning of the library was one of the most important culture crimes committed by the French in Algeria.[xxix] Today, the Algerian government recognizes June 7th as “National Book and Library Day.”

Sarah K. Miles is a global intellectual historian studying anticolonialism, revolution, and print culture in the twentieth-century francophone world. Her current project focuses on transnational print media networks and left-wing militants in France, Quebec, and Algeria in the 1960s and ‘70s.

Endnotes:

[i] Rue Michelet was later renamed rue Didouche Mourad.

[ii] R.N., “L’Incendie de la Bibliothèque Universitaire d’Alger : L’OAS ‘a commis un crime culturel odieux’, ” Le Maghreb no. 7034 (June 9, 2022), 5. Accessed August 17, 2022. https://lemaghreb.dz/images/temp2/edition_du_jours(2891).pdf.

[iii] “Un Appel Sera Lancé à l’Aide Internationale pour la reconstitution…,” Le Monde (November 1, 1962), 4.

[iv] Malika Rahal discusses this period of uncertainty, opportunity, and tumult in her powerful book on Algerian independence. Rahal, Algérie 1962: Une Histoire Populaire (Paris: Éditions La Découverte, 2021).

[v] “OAS reprend sa liberté dès ce soir…reprendre les opérations en visant surtout les objectifs économiques.” Yves Courrière, Les Feux du Désespoir : La Guerre d’Algérie Tome IV (Paris : Fayard, 1971), 637.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] “On n’allait quand même pas leur laisser ‘notre’ culture et ‘notre’ science!” Ibid.

[viii] The Bibliothèque Nationale d’Algérie, founded by the French in 1835, was housed in relatively small edifices throughout the 19th and early 20th century and could not accommodate these acquisitions. It wasn’t until 1958 that the Bibliothèque Nationale opened at its current location, on the boulevard Frantz Fanon. The French had originally intended this to be annexed to the university. After the 1962 attack, the BN recovered surviving volumes from the BU and worked to recreate its collections. Germaine Lebel, “La nouvelle Bibliothèque nationale d’Alger,” Bulletin des Bibliothèques de France, no. 10 (1958), 691-706. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://bbf.enssib.fr/consulter/bbf-1958-10-0691-001.

[ix] “…la destruction, écrit M. Bouayed, restera dans la mémoire des hommes comme l’un des crimes les plus odieux contre la pensée humaine.” “Un Appel Sera Lancé…”, 4.

[x] Frantz Fanon, Les Damnés de la terre (Paris : Éditions Maspero, 1961).

[xi] Malika Yassin, “”مكتبة جامعة الجزائر”.. حريقٌ في الذاكرة, ” Al Araby, Published June 10, 2022. Accessed August 17, 2022. https://www.alaraby.co.uk/culture/%22%D9%85%D9%83%D8%AA%D8%A8%D8%A9-%D8%AC%D8%A7%D9%85%D8%B9%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AC%D8%B2%D8%A7%D8%A6%D8%B1%22-%D8%AD%D8%B1%D9%8A%D9%82%D9%8C-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B0%D8%A7%D9%83%D8%B1%D8%A9.

[xii] “Cet incendie traduit également ce que faisait le régime colonial français pour fermer toutes les portes du savoir au peuple Algérien.” R.N., “ L’Incendie de la Bibliothèque Universitaire d’Alger… ”, 5.

[xiii] “Un Appel Sera Lancé…”, 4.

[xiv] The other members of the committee were as follows: Noureddine Skander (Vice-President), Jean Sénac (Secretary General), Jeanne-Marie Frances (Assistant Secretary), Mme Salah-Bey (Treasurer) and Saâd-Edine Bencheneb (External Affairs).

[xv] Letter from Mahmoud Bouayed to Daniel Guérin. December 24, 1963. Guérin – Comité International pour la Réconstitution. Cote Guérin B84 (F delta 721/96/6). La Contemporaine, Nanterre Universite. Nanterre, France.

[xvi] Printed under Ben Bella, the stamps were issued on June 7, 1965, shortly before the coup d’etat that saw Houari Boumedienne come to power. Emmanuel Alcaraz, “Les Timbres Algériens de 1962 à nos jours, lieux de mémoire de la guerre d’Independence algérienne,” Cahiers de la Méditerranée 91 (2015) : 249-265.

[xvii] Baddari Kamel, “Témoignages sur l’incendie de la bibliothèque de l’université – la part de la philatélie,” Algérie Philatélie. March 24, 2022. Accessed August 9, 2022. https://www.algerie-philatelie.net/article-philatelie-timbres-464.

[xviii] “…tant en livres qu’en argent.” Letter from Mahmoud Bouayed to Daniel Guérin. December 24, 1963. Guerin – Comité International pour la Reconstitution. Cote Guérin B84 (F delta 721/96/6). La Contemporaine, Nanterre Université. Nanterre, France.

[xix] Letter from Mahmoud Bouayed to Daniel Guérin. December 24, 1963. Guérin – Comité International pour la Reconstitution. Cote Guérin B84 (F delta 721/96/6). La Contemporaine, Nanterre Universite. Nanterre, France.

[xx] Letter from Francois Maspero to Giovanni Pirelli. September 6, 1963. FNN 2.45 : Echange de correspondance entre François Maspero et Giovanni Pirelli. Fonds Fanon/Maspero. IMEC. Caen, France.

[xxi] A portion of Sénac’s documents were also donated to the Bibliothèque Municipale de Marseille. Hamid Nacer-Khodja, “Le double destin des archives Jean Sénac, ” Continents Manuscrits. Génétique des textes littéraire – Afrique, Caraïbe, diaspora no. 1 (March 2014). Accessed August 5, 2022. https://journals.openedition.org/coma/221?lang=en.

[xxii] “ L’Association France-Algérie Lance une Souscription Pour la Reconstitution de la Bibliothèque Universitaire d’Alger, ” Le Monde (June 6, 1964), 7.

[xxiii] Mahmoud Bouayed, “ La Bibliothèque Nationale,” Novembre no. 4 (March 1965), 111.

[xxiv] Ibid., 116-117.

[xxv] Ibid.

[xxvi] C. K., “600,000 ouvrages à votre disposition… ” Alger Ce Soir, no. 271 (February 25, 1965), 8.

[xxvii] Ibid.

[xxviii] “Cet incendie est un crime culturel odieux et contre le savoir.” R.N., “ L’Incendie de la Bibliothèque Universitaire d’Alger…” 5.

[xxix] Malika Yassin, “”مكتبة جامعة الجزائر”.. حريقٌ في الذاكرة, ” Al Araby, Published June 10, 2022. Accessed August 17, 2022. https://www.alaraby.co.uk/culture/%22%D9%85%D9%83%D8%AA%D8%A8%D8%A9-%D8%AC%D8%A7%D9%85%D8%B9%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AC%D8%B2%D8%A7%D8%A6%D8%B1%22-%D8%AD%D8%B1%D9%8A%D9%82%D9%8C-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B0%D8%A7%D9%83%D8%B1%D8%A9.

Share the post "Bombs and Books: Franco-Algerian Collaboration and the Reconstruction of the Bibliothèque Nationale d’Algérie"