The Gordian Knot of American politics – Revue de Presse 14 Novembre 2022

Share the post "The Gordian Knot of American politics – Revue de Presse 14 Novembre 2022"

After months of pessimism, the results of Tuesday’s midterm elections were received by Democrats as an extraordinary moment of hope. The much prophesied ‘red wave’, which had appeared so vast on the horizon, crashed upon the shore as nothing more than so much reactionary sea foam. Instead of the Republican triumph in both the House and Senate, seen since the end of the summer as a near certainty, the GOP eked out only a pyrrhic victory in the former and suffered a narrow defeat in the later. As our own Shane McLorrain put it, echoing widely shared sentiments, “there was no “red wave”, merely a “red ripple”.

Election results are always accompanied by both armchair strategizing and partisan recrimination, and the 2022 midterms have been no different.

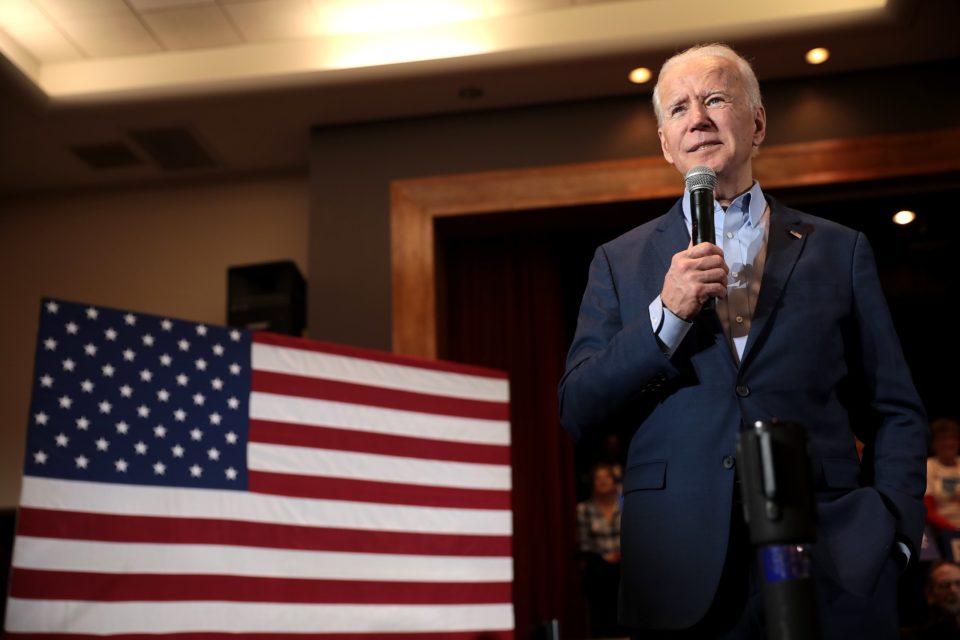

For some among the heterogenous coalition of progressives, liberals, and ‘Never Trump’ Conservatives opposed to the Trump era Republican Party, the results were remarkably positive. In a year marked by rampant inflation and led by a broadly unpopular President, the Democrats’ success in holding onto, and even winning, congressional seats, governorships, and state-wide offices seems to represent a triumph in itself. President Biden, often derided as ineffective and out of touch, has bucked the long-running trend that the Presidents’ party loses seats in midterm elections, granting him “a new lease on life”, and giving his re-election chances a shot in the arm.

So too have progressive victories like John Fetterman’s election to the Senate in Pennsylvania or the election of Maxwell Frost – the United States’ first ‘Gen Z’ Federal official – to the House for Florida’s 10th District emboldened the left of the Democratic party to continue pushing for its transformative agenda. For others, the rout of the GOP signalled the falsity of cynical claims that American voters were motivated purely by self-interest and economics, unconcerned with preserving democracy or abortion rights, or with Republican extremism.

But for others, the midterm results offer only a somewhat bittersweet consolation to a democracy which only narrowly dodged the autocratic bullet. If Democrats have overperformed popular expectations (if not, in fact, the polls), the question remains whether the success of election denialists, and the election of alleged ‘Caesarists’ like J.D. Vance – who believes the United States to be in a “late republican period” – does not nonetheless point to a republic in peril.

For Republicans, the midterms seem set to mark the beginning of a long-anticipated party civil war. Former President Donald Trump, who had earlier attempted to arrogate to himself any credit for midterm success whilst eschewing all blame, has largely been blamed for the party’s defeat, in part because of his support for a series of radical and outlandish candidates. In Trump’s place, more and more conservative strategists and pundits are coalescing around Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, in the wake of his decisive re-election.

Trump himself followed the results with a startling broadside against his aspiring rival, badging the Governor ‘Ron DeSanctimonious’, and accusing him of insufficient loyalty and gratitude for Trump’s past support and of “playing games” by not announcing whether or not he intends to run for President. The former President’s attack was accompanied by staggering claims of election interference in Florida’s 2018 Gubernatorial election, including that he had mobilized the FBI and Department of Justice to aid the Governor.

But partisan post-mortems can obscure the bigger picture insights to be drawn from the results of the election. More than anything, the midterms highlighted not only the cliched fact of American polarization, but the reality that the two great factions in American political life remain resolutely equal, with neither able to secure anything more than the narrowest majority over the other. At least when it comes to winning political office, neither party seems able to overcome its opponent, an impasse which some fear only an external shock will break.

Instead of a succession of decisive majorities, yielding strong and purposive governments, American institutions seem prey to unending division and the indecisiveness which follows. This is the mythical ‘divided’ government of a supposedly less partisan past beloved by American politics’ most facile observers, but without the Cold War era consensus which greased the wheel of historic bipartisanship. The capacity of the American politicians to deliver decisive change in the midst of a world historic crisis of liberal democracy seems remote.

Nor is this a crisis unique to the United States. In France, the ‘Presidential Majority’ government of Emmanuel Macron’s Renaissance Party only narrowly survived a conference vote at the end of October, having failed to secure a legislative majority. Likewise, in the United Kingdom, the economic chaos generated by Liz Truss’ ‘Mini Budget’ led to the fifth change in Prime Minister in six years. Last week Israel faced its fifth election since 2019, and a stable government still appears out of sight. Political deadlock remains the democratic crisis de nos jours.

As Georges Pompidou observed in his 1974 political testament, La Nœud Gordien, democracy appeared to be racing towards “an extreme point where it will undoubtedly be necessary to put an end to speculation and to reorganise the social order. Someone will cut the Gordian Knot. The question is to know whether it will be by imposing a democratic discipline which guarantees liberty or if some strong and helmeted man will draw his sword like Alexander.” If such a statement rang true in the 1970s, it has lost none of its explanatory power in the polarised and paralysed democracies of the 2020s.

In the United States, it is not this year’s midterms which will settle that question, but the Presidential election two years from now. As Tocqueville memorably observed, “For a long while before the appointed time has come, the election becomes the important and, so to speak, the all-engrossing topic of discussion. Factional ardor is redoubled […] the citizens are divided into hostile camps, […] the election is the daily theme of the press, the subject of private conversation, the end of every thought and every action, the sole interest of the present.” All eyes remain fixed on the decisive electoral struggle to come.

Share the post "The Gordian Knot of American politics – Revue de Presse 14 Novembre 2022"