John Stuart Mill, intellectual authority, and the régime of public opinion

Share the post "John Stuart Mill, intellectual authority, and the régime of public opinion"

Much has been written about President Emmanuel Macron’s introduction of the passe sanitaire in restaurants, shopping centres and cultural venues in France. This controversial move has put the spotlight on the ever-growing distrust between France’s intellectual elites and its people.

More generally, the pandemic and the various restrictions have given rise to a proliferation of misinformation, false rumours, and online conspiracy. Pseudo-experts have invaded the sphere of public deliberation, and the distinction between professional and amateur analyses is becoming more and more blurred. As France grappled with a second Covid-19 wave, the release of the documentary Hold-Up, which lends voice to sceptics claiming to reveal an international conspiracy around the pandemic, is illustrative of the rapidity with which disinformation now spreads through the increasing use of social media and crowdfunding.

Interestingly, the lack of clear intellectual authority in democratic societies and its deleterious influence on public opinion is all too reminiscent of a problem John Stuart Mill had already foreseen in the early nineteenth century. “The weakening of the influence of superior minds over the multitude”, he thought, would have irrevocable moral and political implications in a society dominated by “the régime of public opinion”.

Mill believed that the general tendency of modern civilisation was to submerge the individual into the anonymity of the multitude. “Power passes more and more from individuals, and small knots of individuals, to masses”, he wrote. “[T]hat the importance of the masses becomes constantly greater, that of individuals less”.

Mill was primarily inspired in this regard by the French liberal historian François Guizot, whose works he read at length and esteemed. In Guizot’s view, the study of European history revealed the emergence of a new type of power – the social power embodied in the masses. The Middle Ages offered the image of a scattered society, one in which the social bond was inexistent, and one in which individuality sprung forth. The clergy, the feudal nobility and the commons formed disparate societies whose mode of government, laws and manners were independent of each other. The slow fusion of these distinct portions of society into one was what constituted the essential characteristic and the distinctive organization of modern society.

In Guizot’s telling, this transition had been gradual. Starting in the seventeenth century, it first took the form of political absolutism with Louis XIV and his court. It was soon followed by the expansion of the “spirit of free inquiry” in the eighteenth century – an era where everything became at once the subject of study and was summarised in general ideas. Europe’s previously pluralistic societies were now reduced to two elements – a centralised government above, and the mass of the people below. Guizot’s concern was that this centralisation of power and imagined unity of interests could not easily be reconciled with the social multiplicity and local autonomy that had historically existed.

Mill, too, thought that these transformations in the general character of society came with significant downsides.

Crucially, he believed that they would considerably impair the formation of high-quality public opinion. “The individual becomes so lost in the crowd”, he wrote, “that though he depends more and more upon opinion, he is apt to depend less and less upon well-grounded opinion; upon the opinion of those who know him”. In a small society, a merchant may acquire a good reputation solely thanks to the quality of his goods and to the devotion with which he pursues what he undertakes. In a large society, the same tradesman can no longer rely upon the honesty of his labour. His success is now ensured by his ability to stand out from the crowd.

But this, Mill posited, could only be achieved through the development of “marketable qualities”. “A man’s labour and capital are expended less in doing anything, than in persuading other people that he has done it”, wrote Mill.

Just as the power of ideas gains primacy, ideas themselves lose their accuracy and strength. Dishonesty, exaggerations, and provocations surge as competition grows among those who seek the consideration of the crowd. It is in smaller communities that opinions exercise their most salutary influence, yet it is in big ones that they are most needed and followed.

Mill feared that the absence of clear intellectual authority would exacerbate this phenomenon. “When the masses become powerful”, he noted, “an individual, or a small band of individuals, can accomplish nothing considerable except by influencing the masses”. Yet, as intelligence and education spread from the few to the many, the share of these that belong to isolated individuals becomes less influential. Decisions are taken after following the movements of the mass and rely more and more on the “advancing strength of public opinion”. Single minds have little hope of exercising any enduring effect upon the minds and destinies of others. “An established character becomes at once more difficult to gain, and more easily to be dispensed with”, wrote Mill. This, in turn, would debase public teaching and threaten the very possibility of improving public opinion.

It is easy to see how Mill’s diagnosis applies to our contemporary problems. Our world is saturated with information, but in reality, we do not know where to look or to whom to listen. Leading intellectuals no longer possess enough influence to guide the public towards works and opinions of real value. Too often, they retreat into their field of specialisation with little regard for the clamour of the mass. All this eventually breeds anti-intellectualism.

Literature today seems to conspicuously exhibit the ills that Mill was describing. As people read and write more, they no longer read and write carefully. “Nothing is now read slowly, or twice over. Books are run through with no less rapidity, and scarcely leave a more durable impression, than a newspaper article”. This, in turn, affects the very quality of the books produced. Gallimard may be facing an uptick in submissions, and asking would-be authors to stop sending manuscripts, yet there is little chance of a Proust or a Balzac emerging from the crowded field of second-rate writers. Two hundred years ago, Mill bemoaned the increasing volatility that would affect the literary world: “as the difficulties of success progressively increase, all other ends are more and more sacrificed for the attainment of it: literature becomes more and more a mere reflection of the current sentiments”.

Where does this eventually lead us? Mill, after all, was no advocate of a return to an idealised past. Acknowledging these features of the democratic age enabled him to identify what needed to be done to allow independent minds and discerning characters to flourish in a mass society – this being the only way for public opinion to improve and for truth to be collectively attained.

In Mill’s view, greater cooperation amongst the leading intellectuals was key to allow works of real merit to gain more exposure through the validation of those whose names carry real authority. In an age where scientific publishing is rapidly expanding and where alternative channels are opening creating even more competition, this seems particularly relevant. What we may take from him then, is not a desperate yearning for a long-lost aristocratic era. It is a call for experts to work together to establish clear reference points, to help masses discern between creditable information by trusted specialists and pseudoscience by more marginal academics.

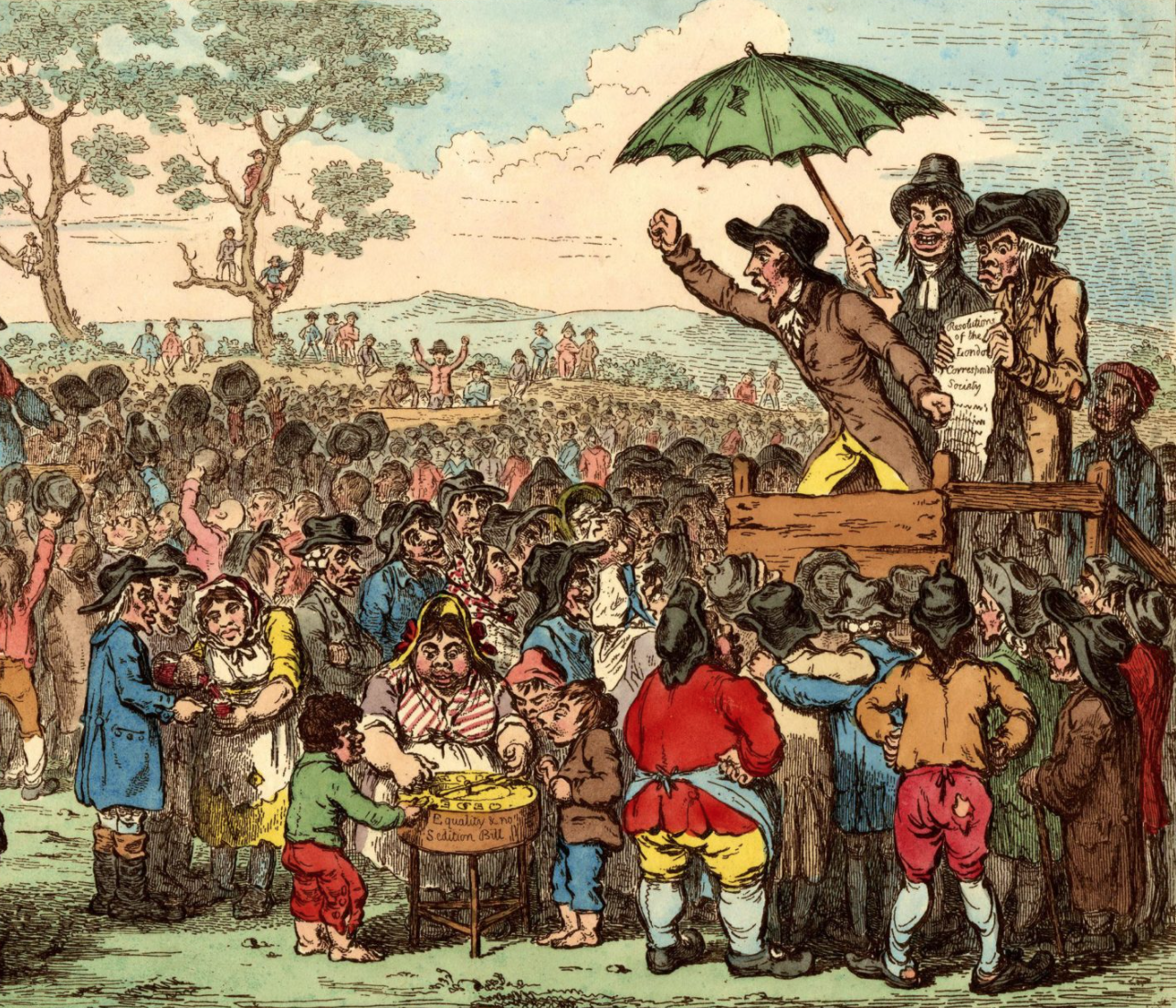

Image credit: Print by James Gillray, Public Domain.

Share the post "John Stuart Mill, intellectual authority, and the régime of public opinion"