Sanction Dysfunction

This is part II of a four-part series on the Russian invasion of Ukraine, focusing on the economic ramifications of the Ukraine invasion. Part I can be found here. Part III will consider potential end points of the crisis. Part IV will examine the psychological aspect of the conflict, including the role fear plays in geopolitics.

War! The West has responded to the Russian invasion of Ukraine with a fresh salvo of economic restrictions. The sanctions have mostly targeted Russia’s financial institutions and some of the country’s elites, including Vladimir Putin and those closest to him. The Russian banking sector has been another major target: assets have been frozen, Russian financial involvement in dollar-based trade has been hit, some key imports and exports have been prohibited, and most importantly, three of Russia’s largest banks have been completely disconnected from the global economic system. Taken as a whole, the sanctions announced on Thursday and in the days since represent a broad barrage, full of sound and fury.

That same day, Ian Bremmer of Eurasia Group, the world’s largest political risk analysis firm, tweeted what many onlookers have been thinking: US and EU sanctions will have absolutely no impact on Russia’s behavior.

His assessment is absolutely correct. Economic punishment will damage the Russian economy, and send financial shockwaves beyond Russian borders. But they won’t be a geostrategic deterrent. Here’s why.

Signifying Nothing

The Russian economy cannot be effectively isolated. Simply put, they supply too much to too many people. The list of countries reliant on Russian exports, such as wheat, natural gas, or crude oil and crude oil products, is long. Geopolitical analyst Peter Zeihan provides a more complete list here, but in broad strokes:

Russia exports massive amounts of oil and natural gas worldwide, which accounts for most of its income and stock of currency. All data points to sanctions on oil and gas being the most effective way to inflict damage to the Russian economy. While some clients, such as China, wouldn’t ever participate in sanctions against Russia anyway, others are close US allies. Between the energy needs of Germany, Hungary, and Italy, the European Union cannot afford to suddenly cease consumption of Russian exports. While America does have a portion of the natural gas necessary to compensate for these interdependencies, and France’s nuclear-based energy sector is also a net exporter and closely tied to other European economies, the economic restructuring isn’t elastic: Europe simply does not have the ability to switch energy sources on a dime, and the resultant price increases would be catastrophic. Because of the European reliance on Russian exports, sanctions on oil and gas were not included in the initial wave of sanctions, nor does it seem likely that they will happen in the near future. In fact, Germany has since increased its purchase of Russian natural gas via the two Nord Stream I pipelines.

While natural gas and oil are the most divisive concern, there are other Russian exports and imports (Italian companies do a lot of business with Moscow) to take into account. These important trade avenues mean that cutting Russia off from SWIFT, a worldwide intermediary for financial transactions, would also devastate some of the countries seeking to impose sanctions. As a result, Russia’s trade with the world continues largely undeterred.

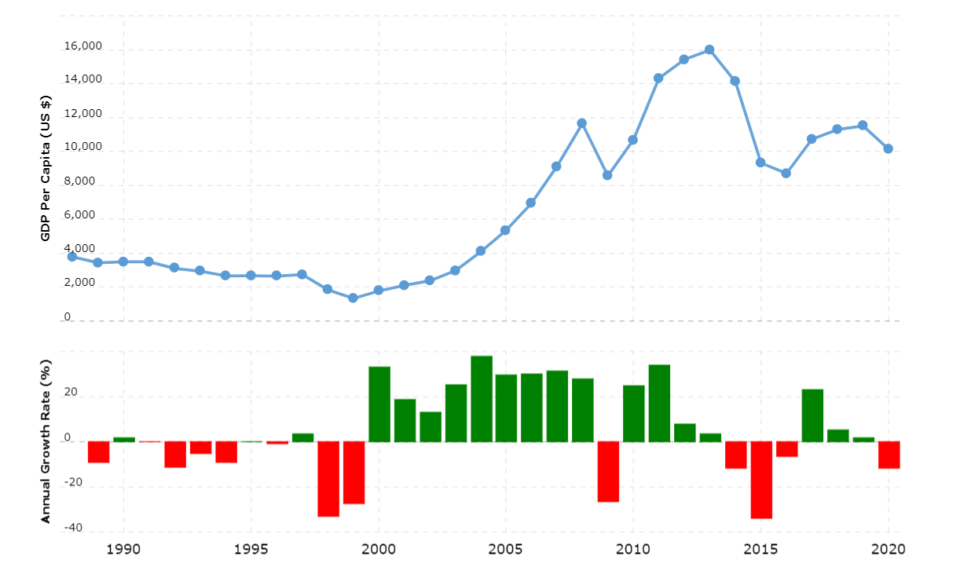

In the event that a comprehensive, damaging package of economic punishments could be agreed upon, the record shows Russia can take the blows. Sanctions have been put in place at various degrees since at least 2014, to no avail. Russian GDP may have plunged to about half its value from 2013 to 2016, but it picked up again in the following years and never went anywhere near even Soviet GDP, which could have constituted a fail-state for Russia.

Russia GDP Per Capita 1988-2022 Credit: https://www.macrotrends.net/countries/RUS/russia/gdp-per-capita

If anything, this shows that Putin does not in the least consider economic damage too high a price for Russia’s geostrategic objectives. Granted, it’s also because his Chinese counterpart has given him a helping hand.

Give’em the old Yuan-Two

As evidenced by a joint statement by Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping on the opening day of the Beijing Winter Olympics, Russia’s partnership with China is hitting its stride, which will no doubt help alleviate the severity of the sanctions. Per Eugene Chausovsky, writing in Foreign Policy: “Bilateral trade hit a record annual high of more than $146 billion in 2021—up from less than $16 billion in 2003 and nearly $110 billion in 2020—with Russia serving as a major source of China’s oil, coal, natural gas, and agricultural imports. At the same time, Russia has increased imported goods, such as electronics and machinery, from China.”

One of the most important endeavors of the partnership, however, is dedollarization, that is to say using alternative currencies in their international trade. According to Mrugank Bhusari and Maia Nikoladze, writing for Atlantic Council: “Russia has begun replacing its dollar reserves with yuans and euros. Between 2013 and 2020, the Russian central bank halved its dollar-denominated reserves. In 2021, it revealed plans to completely ditch all dollar assets from its sovereign wealth fund and increase holdings in euros, yuan, and gold instead, thus acquiring a quarter of the world’s yuan reserves.” This would heavily reduce the impact on dollar-use based sanctions, which President Biden mentioned in his Feb 24 speech outlining sanctions planned by the US.

If trading in anything but dollars could lessen the strain on Russia’s financial institutions, then cryptocurrencies could be a get-out-of-sanctions-free card. Aggressive sanctions might simply encourage Russia to engage in cryptocurrency-based transactions with its essential commercial partners.

Swords to Plowshares

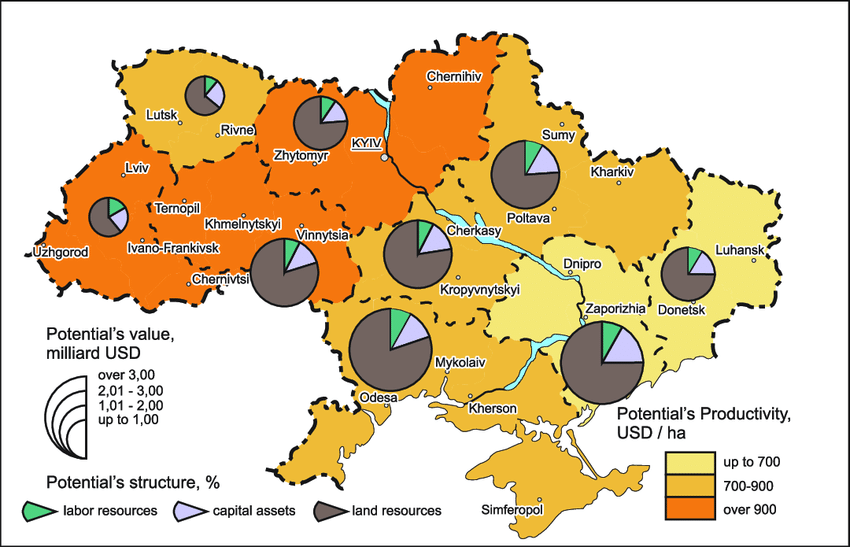

There’s one other thing to consider: The Blitz-like tactics employed by Russia excel when they have territory to swallow. Right now, Putin has effectively launched a lightning speed assault into Ukrainian territory, which means that if he’s not pushed back, whatever resources exist on the conquered territories can be repurposed to either fuel the war effort or fuel Russian economy despite the sanctions. A quick look at a map of Ukraine’s resource and economic potential by region shows that at least one of the Donbas “republics” fabricated by Putin may have already served as an additional breadbasket. The rest of Ukraine is even more profitable in that regard.

Aggregate Resource Potential of Farming Economies in Economic Rayons of Ukraine, 2017 – Credit: Farming economies in Ukraine by resource potential aggregate – Scientific Figure on ResearchGate. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Aggregate-Resource-Potential-of-Farming-Economies-in-Economic-Rayons-of-Ukraine_fig1_321395580 [accessed 26 Feb, 2022]

In fact, Ukraine is a major exporter, largely of agricultural goods. Russia has put its thumb on the scale, halting production and making its wheat exports invaluable. It now controls nearly a quarter of the world’s wheat production, and can apply economic pressure from the Mediterranean to the Indian Ocean. This includes supply lines to strategically indispensable countries such as Turkey, Egypt, and Indonesia. Turkey controls the entry point to the Black Sea; Egypt, the Suez Canal. Combined with Indonesia’s proximity to the Malacca Strait, any one of them could make or break the economic utility of sanctions on Russia. Their continued engagement with Russia as a trade partner removes these strategic avenues from the board as potential pain points for the Russian economy.

To be clear: the steps taken to begin isolating Russia from global financial markets and prevent tech and manufacturing resupply are not entirely inconsequential. But so long as Russia has access to its existing buildup in addition to essential goods, there will be no slowdown of the invasion. So long as the supply of munitions, rations, and fuel endures, the tanks will keep rolling. With 25% of the world’s wheat production, 12% of the global supply of crude oil, and 24% of natural gas reserves in their control, that’s not going to happen anytime soon.

The Good News

So the tanks can’t be stopped with sanctions. But they can be stopped in Ukraine, with weapons. Initial reports suggest that attrition might actually be possible, but not because of the US or the EU: Ukraine is doing a decent job of damaging Russian military hardware. Combined with the economic embargoes on new technologies, essential parts, and other manufactured goods, the Russian armed forces can only rely on the equipment that is currently in their possession. They do not have the ability to efficiently manufacture new tools of war. As a result, every tank lost, and every rifle stolen, is a permanent detriment to the combat capacity of Vladimir Putin’s soldiers.

By all accounts, Russian losses in hardware are far higher than initially anticipated. Given the Fog of War, this is difficult to confirm. But multiple sources suggest that the amount of Russian materiel being captured or destroyed by Ukrainian forces is substantial. Leaked documents from the Kremlin seem to not only confirm the severity of Russian losses, but also suggest that Putin is anticipating far higher losses in the immediate future. This isn’t the Second World War: Putin is working with limited demographics and no capacity for population replacement. If the West keeps sending weapons, the Russian advance might drag on long enough for the already abysmal support for the invasion to collapse completely.

In addition to the stream of weapons, previously recalcitrant EU members are finally warming up to banning Russia from SWIFT, which has been described as a nuclear option, and could possibly be the only effective financial sanction against Russia.

Watching the Road Ahead

That concludes the broad summary of the economic aspects of the war thus far. But as this is an evolving situation, there are still a number of tectonic shifts that could substantially alter the nature of the conflict, mostly relating to other powers.

China’s previously mentioned rapprochement with Russia still contains some unknowns: The PRC has so far stuck to vague commentary. Any evolution in the PRC’s manner of engaging with Russia or even the tone used when discussing the conflict must be monitored closely, particularly given its implications for Taiwan.

In Europe, Turkey faces increased pressure from Ukraine to decide if the Bosphorus and Dardanelles straits will be closed off to Russia. The last few years have seen a degradation of Europe’s relationship with Erdogan, as the Turkish leader took an authoritarian turn. His reaction to the Russian invasion could decide the fate of the war, or at the very least significantly reduce how much room Russia has to maneuver.

Finally, other nuclear powers must decide how to react to Putin’s insinuations that retaliatory nuclear strikes were not off the table. France has led the charge, engaging Russia in a more belligerent way than most major powers have yet dared.

As the siege of Kyiv begins, good night, and good luck.

Shane McLorrain and Noé Sainderichin

2 Comments

Really great article Shane. You make a complicated situation much easier to comprehend.