The Source of Our Restlessness

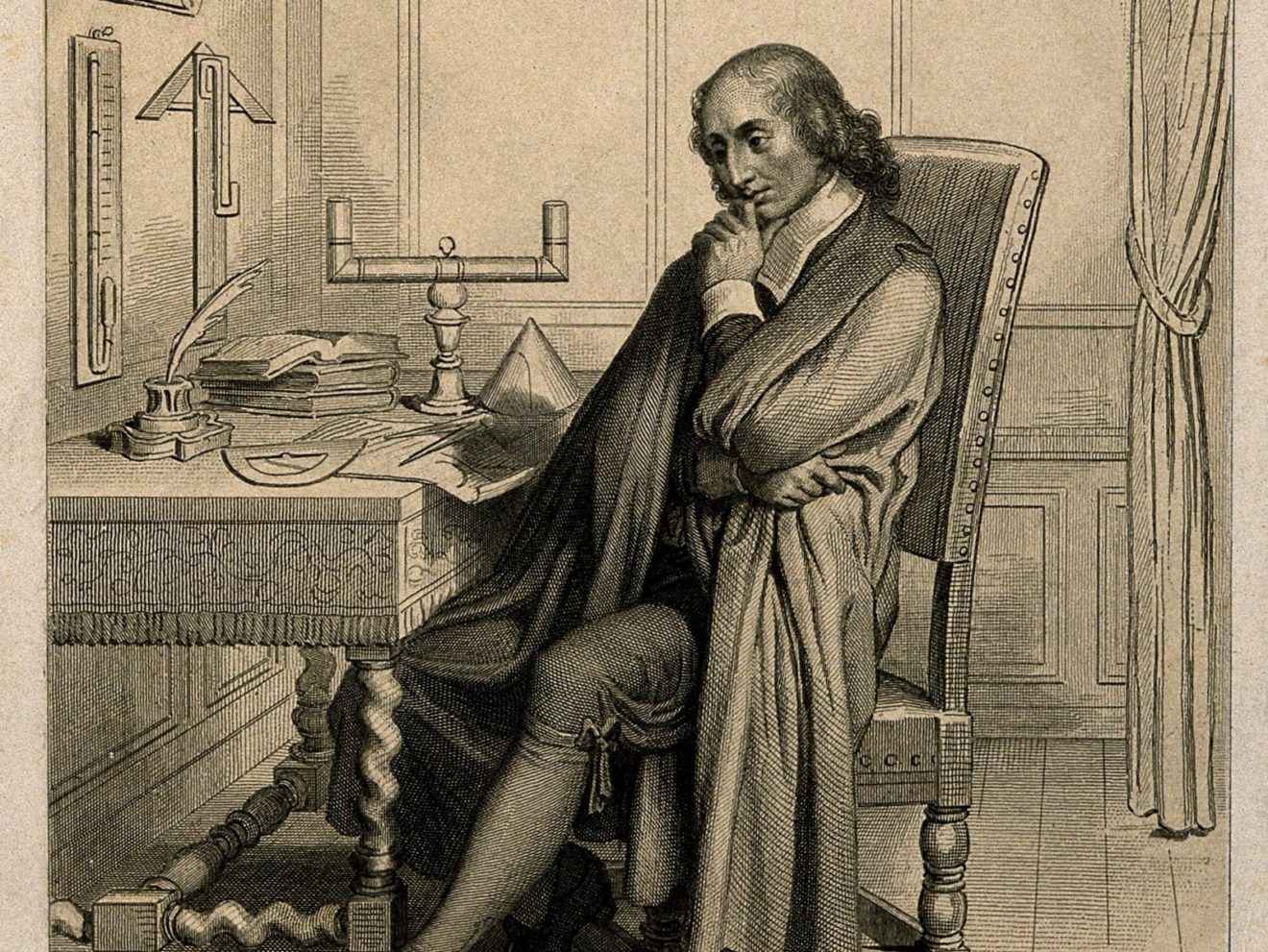

Blaise Pascal, seated at his desk. Line engraving by J. Bein.

“We just cannot get a break.” Surely that is the universal sentiment of the past year. Yet in trying to rationalize a catastrophic year, there is something we can do moving forward: stop guessing what will be the next catastrophe. For the sarcastic observers, “What will this month hold for us?” has become the new “Have you seen the weather?” This phenomenon speaks to actual catastrophe as much as to our restlessness in expecting it.

Turn to Alexis de Tocqueville, and Democracy in America tells a reassuring tale instead: events can get better or worse—but events are only part of the picture. Fortunately, historical events will pass; whereas our temperament is here to stay. In Tocqueville’s world, people’s inclinations are what you can actually change about society. The fatal flaw of Western democracies is restlessness.

The good news is that we are aware of our restlessness. Open a newspaper during the pandemic and there is a chance you come across this adage by Blaise Pascal: “All of humanity’s problems stem from man’s inability to sit quietly in a room alone.” Submerged by the deafening convergence of globalization and rapid information, we feverishly long to “disconnect,” and we idealize that person who sits placidly through the storm.

Funnily enough, Tocqueville was already asking these same questions back in the 1830s. For him too, the author of Pensées was the model of patient abnegation: “When I observe [Pascal] tearing his soul away, so to speak, from the concerns of life to devote it entirely to this research and severing prematurely the ties which bind his soul to his body, to die of old age before his fortieth year, I stand aghast and realize that no ordinary cause can produce such extraordinary efforts.” (II.I.10) Pascal was able to turn away from the mundane and produce a timeless text because he was unconcerned with temporal needs. He worked ascetically and neglected his health. Pascal, Tocqueville writes, selflessly gathered “all the powers of his intellect for a deeper discovery of the most hidden secrets of the Creator.”

The tragedy with Democracy in America is setting down the book, looking at the horizon, and realizing there probably will not be many figures like Pascal again. Few would give their life for philosophy. Still, Tocqueville explains that aristocratic societies gave birth to countless other prodigies who, without quite making that sacrifice, retreated away from bustling cities to patiently meditate abstract ideas. (He does of course concede that this exercise is reserved to the privileged few.) These ideas “encourage the natural impulse of the mind toward the highest regions of thought which then has a natural inclination to raise the love of truth to a sublime, almost divine level.” (II.I.10)

Tacitus wrote that fifteen years is a long time in a human’s life: Quindecim annos, grande mortalis aevi spatium. Chateaubriand famously dedicated three times that to literature. Today, our life expectancy is even longer—but somehow we just do not have the time. Somewhere along the road, we decided that enjoying many small novels is more satisfying than sifting through a few monumental works. So we changed the way we read, the way we watch artistic performances; time took on a different quality. We turned away from the artisanal “aristocratic” model of production to entertainment that is mostly accessible, rapid, but perhaps hollow. We stopped painting frescoes in the Sistine Chapel, and felt it was easier to retouch them.

Tocqueville suggests this shift towards rapid entertainment occurred after the succession of “democratic revolutions” in the United States, France, and parts of continental Europe. Elsewhere, monarchies were democratized from within. The equalizing momentum from the American and French revolutions irreversibly gave way to opportunity, economic mobility, and progress in many regards. The rigidity of feudalism was replaced at the other extreme by a race for riches and productivity. Idle aristocrats suddenly saw competition from frenetic social-climbers—the quintessential embodiment of this dynamic being Napoleon Bonaparte. Tocqueville describes the democratic overhaul with mixed sentiments of curiosity and regret:

Most men in these nations are very eager for immediate material pleasures and, as they are always dissatisfied with the position they occupy […] any novel method which leads by the shortest route to wealth, any machine which lessens work, any means that diminishes the cost of production, any discovery which smoothes the way to increased pleasure, seems the most magnificent work of the human intellect. Amid this widespread upheaval […] where could we find the tranquility needed for deep intellectual investigations? (II.I.10)

The political and economic spheres, once democratized, were mirrored by a leveled but prolific cultural production. Eventually, these habits durably altered people’s “feelings and ideas” towards a state of tireless ambition. The nineteenth century was at once the century of revolutions, the reign of the bourgeoisie, and the Belle Époque. In wanting political change, we signed up for all of its side effects. We embraced restlessness as a philosophy of life.

The second piece of good news, decidedly, is that restlessness is a choice we can mitigate. And it does not require the solitary genius of Montaigne in his Essays or William Butler Yeats in The Tower. If you are able to do so, seize a lull in this pandemic to spend a day in the countryside. Go walk in the fields. Rent the shed in the woods that you always dreamt about. Currently, many of us treat the year 2021 as just another one of those television shows, restlessly awaiting the next episode with unhealthy curiosity. And it serves no purpose but to make us collectively irascible. Alas, I now put down my pen. Yes, I’m still watching …

Photo Credit: Line engraving by J. Bein (Wellcome Images) via Wikimedia Commons (CC by 4.0)

Image cropped for layout.

1 Comment

Finally, my grand grand grand child is come to reflourish my France