Civic Duty and Racial Tyranny: Reading Tocqueville at the Limits of American Democracy

Share the post "Civic Duty and Racial Tyranny: Reading Tocqueville at the Limits of American Democracy"

Almost two years ago, on a February day in 2020, three men chased Ahmaud Arbery through a coastal Georgia suburb with pick-up trucks and guns and killed him. Arbery was jogging, unarmed. The three men—Travis McMichael, his father William McMichael, and William Bryan—took Arbery’s life, their defense attorneys claimed, out of a sense of civic responsibility. As attorney Robert Rubin put it, “This case is about [Travis] McMichael’s duty and responsibility to himself, to his family, and to his neighborhood.”

Almost two years ago, on a February day in 2020, three men chased Ahmaud Arbery through a coastal Georgia suburb with pick-up trucks and guns and killed him. Arbery was jogging, unarmed. The three men—Travis McMichael, his father William McMichael, and William Bryan—took Arbery’s life, their defense attorneys claimed, out of a sense of civic responsibility. As attorney Robert Rubin put it, “This case is about [Travis] McMichael’s duty and responsibility to himself, to his family, and to his neighborhood.”

A similar sense of duty allegedly called to seventeen-year-old Kyle Rittenhouse in late-August of 2020. Following the police shooting of Jacob Blake in Kenosha, Wisconsin, Rittenhouse responded to an online call from a Kenosha militia group to “protect our lives and property” from protestors who had gathered to condemn the shooting of Blake, and to denounce state violence against black people more generally. Rittenhouse, whose mother drove him from their Illinois home across state lines while her son cradled an assault rifle, ultimately shot three of these protestors. One of them survived. The other two, Joseph Rosenbaum and Anthony Huber, did not.

Like many skeptical observers of these cases—including, apparently, the jury in the Arbery case—I cannot but recoil at the defense’s use of terms like “duty” and “responsibility.” The defense’s employment of these terms obscures more elemental and less-palatable motivations involved: the murderer’s sadism, combined with a cynical understanding that often one can kill black people in America and get away with it. Nevertheless, it is important to note how often and how effectively the killers of black people in the United States (or, in Rittenhouse’s case, of white people who protest the killing of black people) cite duty and civic responsibility as the primary justifications for their crimes. Whether or not the people who make these arguments really believe them is not a particularly relevant question. The more important question is why so many people in the United States persistently repeat and act upon the political and social premise that civic responsibility entails militantly policing and killing black people.

Recent studies of the pervasiveness and growing power of white supremacist thought and action in the United States have tended to emphasize twentieth century phenomena and texts as the principal foundations for this kind of violent racial civic mythos: mid-century reactions to the Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War, changes in immigration law, and the infamous 1978 novel The Turner Diaries by William Luther Pierce, to cite just a few. While studying these events and texts can help us understand the particular shapes that contemporary white supremacist movements have taken, they do not explain the richness or the depth of the ideological entanglement between civic duty and anti-black violence in the United States. These entanglements are rooted far deeper in U.S. history, and their enduring entrenchment is reflected in many of the central, foundational texts that comprise early American political development and critique.

Among the texts in which this entanglement between civic duty and anti-black violence can be found is Alexis De Tocqueville’s canonical 1835 Democracy in America—one of the first great political critiques of U.S. democracy authored by a non-American. Tocqueville’s exposition of American citizens’ violent racial duties is singularly forthright, in a way that the Anglo-American founding fathers could not be, concerned as they were with crafting a state for posterity. As such, critically reading this text in our own violent and precarious moment can train us to see the workings of this powerful social narrative not only on the explicitly racist margins of American political life, but in its ideological mainstream.

It must be noted that ideological entanglements between anti-black violence and civic duty far pre-date the United States of America, and they can be found in the history of any society in which plantation slavery existed throughout the colonial Americas. Moreover, these ideological entanglements were forged in direct relation to the extraordinary violence necessary to establish and maintain plantation slavery’s commercial viability, which in turn rested on the maintenance of the extreme racial dominance hierarchies that defined slavery in the Americas. As such, it is important to understand the social world that Tocqueville attempts to describe in Democracy in America as fundamentally shaped by two centuries of extreme racial terror and social violence.

Tocqueville directly addresses these violent racial dominance structures within the first volume of Democracy in America, in a chapter entitled “Some Considerations on the Present State and the Probable Future of the Three Races that Inhabit the Territory of the United States.” For reasons that will soon become obvious, this is not one of the more popular chapters for contemporary Tocquevillians who would construe Tocqueville as a democratic visionary. Nevertheless, the chapter contains within it Tocqueville’s most strident warning about the future of American democracy. In a section devoted to the relationship between white and black people in the United States, Tocqueville writes: “The most dreadful of all the evils that threaten the future of the United States arises from the presence of blacks on its soil.”[i]

One needs no extra context to note how clearly this sentence betrays Tocqueville’s steadfast commitment to both the ideal and the continued material existence of American white supremacy. But tracing how Tocqueville arrives at this conclusion allows us to see just how powerfully the forces of racial tyranny that structured American social life can bend the democratic imagination to their own insidious purposes.

Tocqueville begins this section by attempting to build a wall between the forces of democracy—that which he describes as existing between the masses of white people in the United States—and the forces of tyranny that define the relationship between white American power and black and indigenous people. As he makes clear at the beginning of “[Considerations] on the Three Races,” the relationships between the three races “touch on my subject, [but] do not enter into it. They are American without being democratic, and it is above all democracy that I wanted to portray.”[ii]

Try as he might to keep the gate between Anglo-American democracy and Anglo-American tyranny barred and sealed, however, Tocqueville’s actual description of American racial tyranny suggests a messier reality. This is particularly true in the section from which his prophecy about the “black presence” emerges, which is aptly entitled “Position that the Black Race Occupies in the United States; Dangers Incurred by Whites from Its Presence.” Where Tocqueville is at his best throughout Democracy in America, so too is he at his best in this section —describing the relationship between social structure and the “mores” of American white people.

Because slavery had become so deeply entwined with the phenomenon of race—a fact that distinguished modern Atlantic slavery from that of the ancients, according to Tocqueville—he did not believe that the formal abolition of slavery would diminish the power of anti-blackness and white supremacy as engines of social hierarchy. If anything, Tocqueville argued, the abolition of formal slavery would only strengthen white people’s social, cultural, and spiritual commitment to anti-blackness, as these were the only realms in which they could enforce their separation from and superiority to what he calls the “ignominy” of blackness in American society. The persistent and virulent anti-black racism of the formally “free” North proved the point for Tocqueville: “[Racial] inequality is engraved in mores in the same measure as it is effaced in the laws.”[iii]

Readers familiar with Democracy in America will know that for Tocqueville, social and cultural mores are precisely those things that hold a democracy together. But even as he initially claims that the tyrannical forces of racial terror in the United States are “American without being democratic,” Tocqueville ultimately proffers exactly the opposite observation. Ruminating on the extent to which white Americans had democratically committed themselves to the “aristocracy” of whiteness, Tocqueville makes this assertion:

A despot coming to intermingle the Americans and their former slaves under the same yoke would perhaps succeed in mixing them: [but] as long as American democracy remains at the head of affairs, no one will dare to attempt such an undertaking, and one can foresee that the more the whites of the U.S. are free, the more they will seek to isolate themselves.[iv]

The tyranny of race in America does more than “touch on” democracy here; it persists because of white democracy. White people, according to Tocqueville, had developed anti-black mores and social patterns running deeper than any law, and thus, if left to their own devices, would reproduce anti-black social structures in perpetuity. Only a coercive tyrant willing to impede the democratic relations between white people could ever hope to change their tyrannical relationship to black people.

But, careful observer that he was, Tocqueville could not quite rest at this description of the relationship between American democracy and American racial tyranny, particularly in his account of the plantation societies of the U.S. South. While Tocqueville blithely predicts that white people would simply—and democratically— forcibly remove the “small nomadic tribe” of black people in the North, this was not logistically feasible in the South (while he admired the efforts at ethnic cleansing carried out by the American Colonization Society, he did not see them as practical). Nor did he consider the status quo of plantation slavery an ideal solution, partially on simple ethical grounds. He describes plantation slavery as “the order of nature reversed,” a system in which “humanity cries and struggles in vain under the laws.”[v]

More important for Tocqueville, however, is what slavery was allegedly doing to white people. Tocqueville argues that the mass enslavement of black people in the South had corrupted the democratic mores of white southerners, such that they “scorn not only work, but all the undertakings that work makes successful.”[vi] The American reverence for work constituted one of the key threads in the democratic fabric of American life for Tocqueville. As such, Tocqueville describes a deterioration of democratic mores when he declares that “within this aristocracy [of whiteness in the South], one could encounter poor men, but not workers; misery appeared preferable to industry.”[vii]

In essence, the universal white commitment to maintaining the borders of whiteness meant that the tyrannical relations of race had subsumed and corrupted work and thrift, such that these were no longer the driving virtues of southern America. Consequently, the South’s very status as a democratic polity was being undermined. Thus, per Tocqueville’s narrative, anti-black tyranny was a fundamental component of white democracy; but this commitment to anti-black tyranny was also, particularly in those places where white people actually came into contact with black people, eroding the fabric of white democracy itself.

All of this might suggest that Tocqueville is building a case for how slavery and the racist mores of white people constituted the greatest threat to the future of American democracy. But he is not. Rather, he leverages all of his careful observations to construct a crude racial mythology, which collapses all of his analysis of the anti-democratic functions of American democracy into an endorsement of American racial tyranny.

Tocqueville ultimately argues that whatever the deleterious effects of slavery upon the democratic fabric of the nation, one cannot blame American white people for continuing to reproduce it. This is because slavery, according to Tocqueville, was all that was keeping black people from annihilating white people and driving them from the land. His reasoning was simple: should black people ever attain the least opportunity to organize, to educate, and to arm themselves, they would inevitably seek to subject their former enslavers to the same tyranny and violence to which they had been subjected. “[The] same abuses of power that maintain slavery today would then become the source of the greatest dangers that the whites had to fear,” Tocqueville declared.[viii] By extension, the consequence of a successful black freedom struggle was that white southerners would go the way of the “Moors of Spain,” massacred and driven out of the U.S. South for good. Abolition, furthermore, would do nothing to prevent this outcome; Tocqueville anticipated white people would act just as they had in the North by refusing to allow free black people access to the levers of power, while the marginal freedoms allowed by abolition would only increase opportunities for black people to organize and to annihilate the white population.

Thus, however careful and nuanced Tocqueville may be in his descriptions of white American cultures in Democracy in America, what lies beneath it all is a basic story of existential, inexorable, and zero-sum racial warfare. “Until now,” Tocqueville declares, “everywhere that the whites have been most powerful, they have held Negroes in degradation or in slavery. Everywhere that Negroes have been strongest, they have destroyed whites; this is the only account that has ever opened between the two races.”[ix] And so it would be, apparently, in perpetuity. For this reason, Tocqueville insists that he “cannot find the indignation to stigmatize the men of our day” because they were not the ones who “introduced servitude”—and the inexorable state of perpetual race war slavery spawned—to the Americas:

If it is impossible to foresee a period when Americans of the South will mix their blood with that of the Negroes, can they, without exposing themselves to perishing, permit the latter to come to freedom? And if they are obliged to want to keep them in irons to save their own race, ought one not excuse them for taking the most efficacious means to succeed in that?[x]

The narrative logic of these rhetorical questions rests on one phrase: “to save their own race.” What Tocqueville implicitly suggests in these questions is that race and nation are one and the same—that whether or not democracy flourishes in America is less important to the nation’s destiny than whether its dominant race can be preserved as such.

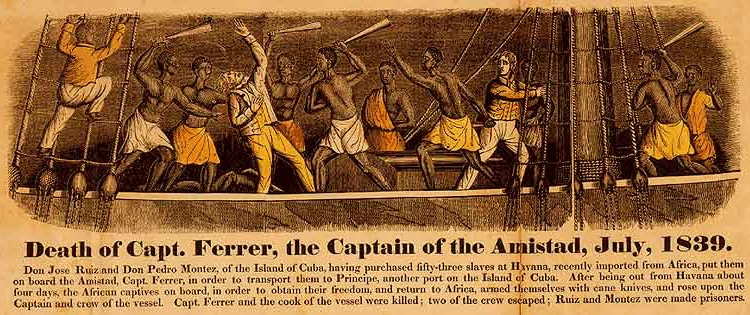

Of course, Tocqueville was right to suspect that black people in the U.S. South might want to seek violent redress vis-à-vis those who committed and profited from the structural atrocities of plantation slavery. The myriad historical instances of black diasporic people violently resisting slavery in the Americas prove this point. Moreover, less than a decade before the publication of Democracy in America, the black American abolitionist David Walker published his canonical 1829 Appeal to the Colored Citizens of the World, in which he explicitly called upon black people in the United States to see the mass of white Americans, particularly enslavers, as their “natural enemies.”

Walker saw this “natural enmity” as a structural relationship between white and black people which must be understood and redressed by black people in order for black folks to know and practice freedom and self-determination. Tocqueville’s narrative, however, reduces all of black life to a reactive and genocidal desire—a desire completely and utterly oriented towards white people and whiteness. In doing so, Tocqueville tells us nothing interesting about the political lives or dreams of black people in the United States. However, he presents a lucid projection of his own normative conception of the relationship between race, nation, and democracy in the United States. In the end, for Tocqueville, American national destiny—and thus the destiny of democracy in America—depends upon white people suppressing black freedom in order to assure white survival.

There is a kind of resigned melancholy in this racial-national narrative Tocqueville presents. Yes, slavery is “the order of nature reversed,” a violent and degrading social force that terrorizes and violates black people as its first principle and erodes the possibility of democracy even among white people; but who can blame the enslavers? Don’t they deserve to live, too? Isn’t their primary responsibility to protect their kin and country? Can one blame them for this?

Variations on this performance of racial-national melancholy radiate forward and backwards in time across the political thought of the United States and the Atlantic world, always to the same effect. Thomas Jefferson offered his own infamous expression of this narrative near the end of his life: “We have the wolf by the ear, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go,” he lamented. “Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.”[xi] These racial parables pose as mere descriptions, but they are in fact mythic narratives that hold, compel, and constrain the imagination of their listeners, offering them the role of either wolf or hunter. Those who have structural access to the role of hunter are naturally more excited to see their world in such terms, and to invest their sense of purpose in such narratives.

It is an easy enough thing to declare that people should not conceive of themselves in accordance to such narratives, but this is about as useful as declaring that people should stop eating cheeseburgers. As political philosopher Cedric Robinson writes, “Without myths, that is, without meaning, consciousness is set adrift into terror.” Here, Robinson echoes the author Richard Wright’s concern with the “spiritual void” into which western imperialism had cast the colonized and enslaved masses of the world. Recovering spirit from the clutches of that void, Robinson suggested, was one of the great struggles for the variously oppressed masses everywhere, and one of the great triumphs of the Black radical tradition. But for such myths to resist their appropriation by forces of domination, they must be imbued with a “critical commitment”—a commitment that can only emerge from a consciousness that believes it is “capable of re-creating meaning.”[xii] In other words, for a social myth to provide the basis for a more just, equitable, and free social future, the people who reproduce this myth must be able to truly reimagine how this myth applies to their own ever-shifting social conditions and epistemologies.

It remains to be seen whether the foundational myth of the American nation can be resolved or “re-created” so as to really animate the struggle for something resembling the triumph of democratic life over the forces of tyranny. For this to happen, its fundamental enmeshment with the spiritual fetish of racial-martial responsibility and the material forces of racial tyranny must be confronted, at precisely those junctures where Tocqueville’s democratic imagination retreats into crude race war fantasies. Many have tried to do precisely this, but they have usually found themselves outflanked by this myth’s baseline—its perpetual call to the frontlines of the race war. Nevertheless, the tyrannical power of this martial hail cannot be ignored, nor can it be cast onto the disreputable fringes of American political life. It is as American as apple pie.

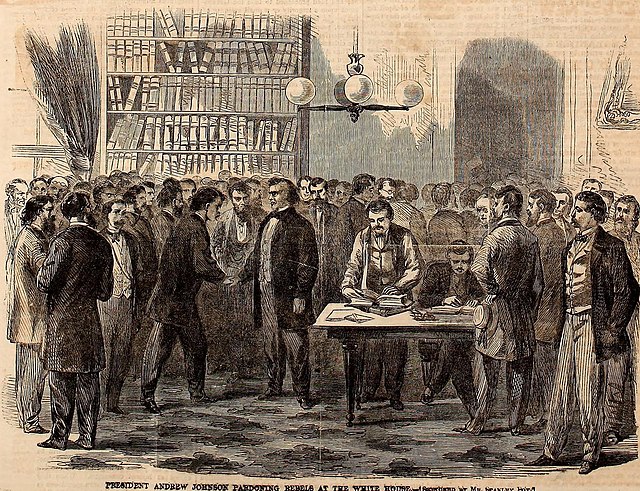

Photo Credits: Men of Color Civil War Recruitment Broadside, 1863 via Wikimedia Commons, President Andrew Johnson pardoning Rebels at the White House, sketched by Stanley Fox via Wikimedia Commons, Amistad Revolt, via Wikimedia Commons.

[i] 326.

[ii] 303.

[iii] 330.

[iv] 342.

[v] 348.

[vi] 330.

[vii] 335.

[viii] 341.

[ix] 328.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Thomas Jefferson to John Holmes, Apr. 22, 1820, in P.L. Ford, The Works of Thomas Jefferson, vol. 12. (Putnam’s & Sons, 1904). 158-9.

[xii] Robinson, Cedric. Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition. UNC Press, 2000 (1983). 301-2.

Share the post "Civic Duty and Racial Tyranny: Reading Tocqueville at the Limits of American Democracy"