Waging war on American democracy

Review: Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, A Violent Peace and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books)

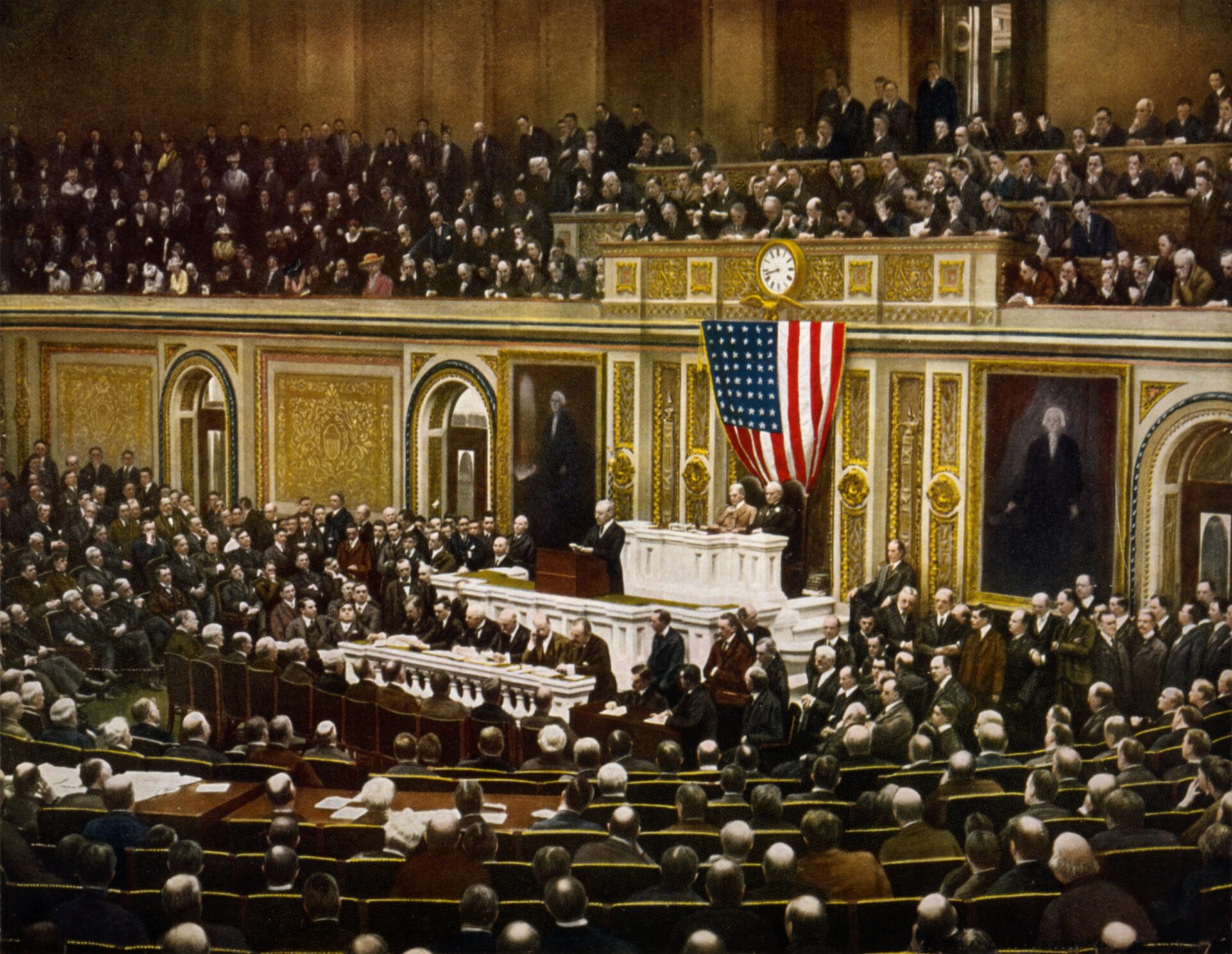

“The world must be made safe for democracy.” That was American president Woodrow Wilson’s most prominent argument when he asked the United States Congress for a declaration of war on Germany in April 1917. But Wilson, who months before had won re-election while campaigning on a pledge to keep the country out of the European conflict, might just as well have asked Congress for a declaration of war on American democracy. Wilson finished his address to Congress by stressing ominously that “if there should be disloyalty” it would be “dealt with with the firm hand of stern repression.” As Adam Hochschild demonstrates convincingly in American Midnight: The Great War, A Violent Peace and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis, Wilson proved all too true to his word.

A progressive Democrat when first elected to the presidency in 1912, Wilson presided over the “greatest assault on American civil liberties in the last century and a half,” Hochschild writes, with “few regrets over that contradiction.” The assault targeted such overlapping disfavored groups as anti-war dissenters, unions, socialists, immigrants, and anarchists, along with Americans of German ancestry. It included “mass imprisonments, torture, vigilante violence, censorship, killings of Black Americans, and far more.” This is the “forgotten crisis” of Hochschild’s title sub-title, a side of American history “not marked by commemorative plaques, museum exhibits or Ken Burns documentaries.”

Although the United States had by far the world’s largest economy in 1917, it was “startingly unprepared” for war. Its army was only the seventeenth largest in the world, smaller than that of Portugal. Nearly a year passed before large numbers of Americans were fully ready for combat. Then, months later, in November 1918, the fighting in what was then termed the “Great War” ended with an armistice. But the domestic war within the United States continued into 1921, the year Wilson’s second term ended. Shining light on the full period 1917 to 1921, Hochschild provides roughly equal treatment to the war and post-war years.

During this time, what he terms the “raw underside of our country’s life,” including such phenomena as racism, anti-immigrant hostility, vigilante justice, and contempt for the rule of law, had never been more revealingly on display. But Hochschild makes clear that these phenomena had been part of American history for decades. When the United States joined the conflict in Europe, however, America’s long-standing racism and nativist hostility to immigrants blended seamlessly with an equally deep-seated hatred of “any challenge to the power of business and industry,” particularly the challenge of labor unions and their Socialists backers. American entry into World War I “provided business with a God-given excuse to stop workers from organizing,” Hochschild writes.

Hochschild’s best known work is the award-winning King Leopold’s Ghost, the story of how Belgian King Leopold II used violence and coercion to gain control of the Congo in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He is also the author of two works reviewed on my personal blog, To End All Wars, dealing with the reaction to the First World War within the belligerent European countries, and Spain in Our Hearts, the American participation in the Spanish Civil War. Returning to the era of the First World War in American Midnight, Hochschild again shows himself again to be a formidable storyteller, delivering a steady stream of anecdotal evidence in sharp, almost bullet-point form. The result, a withering indictment of widespread governmental abuse at all levels, revolves around a colorful collection of villains and victims, along with a few heroes who resisted the massive assault on civil liberties and American values.

Woodrow Wilson requests a formal declaration of war on Germany before a joint session of Congress, 1917.

The central figure in American Midnight is the inscrutable President Wilson. Although Wilson had initially hoped to keep the United States out of the conflict that broke out in Europe in 1914, he became convinced that United States participation was necessary to shape the post-war order. Wilson hoped that an international organization to ensure a lasting peace – what came to be known as the League of Nations – would emerge from the carnage of the war. There is a suggestion of pretext in Hochschild’s interpretation of the decision to go to war. Although Germany, “with some reason,” was blamed for having started the war, “no one had attacked the United States,”– there was no analogue to the German invasion of Belgium three years earlier or to Pearl Harbor a quarter century later. German ships interfered with American shipping and killed American citizens, most dramatically in the sinking of the British passenger line Lusitania in 1915, costing 128 American lives among the nearly 1,200 who died, but, as Hochschild points out, Germany had tried to warn potential passengers of the risk of traveling on the Lusitania, a ship also carrying “173 tons of munitions, including artillery shells and 4.2 million rifle bullets.”

Yet, in his appeal to Congress, Wilson argued that the role of belligerent had been thrust upon the United States, in keeping with what Hochschild terms the “pretense that the United States was an innocent victim drawn into the conflict against its will.” Across the country, people were “thrilled by the idea that the country was somehow defending itself.” But if the United States was defending itself in Europe, it was simultaneously being “fatefully transformed” at home.

One of the most prominent members of Wilson’s administration who helped to effect that transformation was Wilson’s Postmaster General Albert Burleson, who became “America’s chief censor,” with powers “seldom wielded by any single government official before or since.” Burleson’s powers emanated from the Espionage Act, passed in June 1917, which had little to do with spying and defined almost any sort of opposition to the war as criminal. The act gave the Postmaster General authority to declare any newspaper or magazine ‘unmailable” at a time when “there was no other way to distribute publications nationally.” Burleson’s first target was what he termed “offensive negro papers that constantly appeal to race and class prejudice,” but he went on to use the Espionage Act primarily as a “club to smash left-wing forces of all kinds.”

Burleson went after publications that depended entirely upon the mail, “foreign-language papers, journals of opinion, and Burleson’s prime target, the socialist press.” He declared one socialist publication, The Rebel, unmailable after it exposed exploitation on a cotton farm owned by his wife. He went after the best known socialist monthly, The Masses, “one of the liveliest journals the United States has ever seen.” A trial against The Masses ended in an acquittal but still led to the magazine’s permanent disappearance.

The Wilson administration also benefited from the services of Major Ralph Van Deman, who led a newly established surveillance unit within the Department of the Army, set up to spy on American citizens. The unit recruited Pinkertons and other private detectives with experience working for corporate clients against labor organizers. It kept files on hundreds of thousands of Americans, tapped phones, compiled ethnic breakdowns of the groups the units placed under surveillance, and maintained informants and secret infiltrators.

Eager to believe the “wildest of rumors,” Van Deman became convinced that Germany was inciting the Black population of the United States. Among the African American targets of his surveillance was the Reverend A.D. Williams of Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta, whose grandson, Martin Luther King, Jr., became both a preacher in the same church and the subject of another era’s government surveillance under FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. But Van Deman’s most obsessive target was the Industrial Workers of the World, known as the “Wobblies,” a relatively small syndicalist labor group to which Hochschild returns repeatedly throughout American Midnight.

Even though their numbers never exceeded 5% of American union members, the Wobblies were a convenient bogeyman for anti-labor politicians and businessmen, with the war presenting a “welcome chance to crush them.” To that end, Van Deman benefited from the work of one Leo Wendell, an infiltrator who went by the name of Louis Walsh. Reporting directly to Van Deman, “Walsh” posed as a mechanic and Wobblie activist, particularly in Pittsburgh area steel mills. Taking pride in his many Wobblie friends and how much they trusted him, he was elected to the strike committee when the steelworkers went on strike and arrested several times, often to great fanfare, but usually released shortly thereafter.

The Wobblies were subject to the largest civil trial in the history of the United States in the summer of 1918, with 112 defendants accused of seditious speech; none was charged with violent acts. After about an hour of deliberations, the jury rendered guilty verdicts for all defendants, permanently crippling the union. The IWW “would never again be a significant force in American life,” Hochschild writes. When Wendell provided the Department of Justice with insider information on Wobblies in Pittsburgh, the information went to a 24-year-old J. Edgar Hoover, whom Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer had just appointed to head a new, internal “Radical Division” within the department.

In that position, the young Hoover engineered a nation-wide series of raids and arrests that have gone down in history as the “Palmer Raids” but in Hochschild’s view would better be called the “Hoover Raids”, and which he describes as a “domestic war the likes of which the United States had never seen.” The raids were ostensibly a response to a spate of bombings across the country in June 1919, targeting men in power, including Attorney General Palmer, none of whom was hurt. The bombings may have been the work of members of a “tiny, shadowy sect of Italian American anarchists,” but the actual perpetrators were never identified. Hoover and Palmer used the raids for broader purposes, to arrest and deport a wide variety of Socialists, union members, suspected anarchists, and other subversives for “political advantage . . . regardless of the lack of evidence connecting them to the bombings.”

As Palmer’s “determined deputy, quietly wielding influence beyond his years,” Hoover engineered the raids, which began on November 7, 1919, the second anniversary of the Bolshevik coup in Russia. It was the time of the “First Red Scare” in the United States, when business and political leaders feared that Bolshevism was spreading to American shores. The raids took place in more than a dozen cities in the Northeast and Midwest. They enhanced Hoover’s stock within the Department of Justice, as well as providing a political boost to Palmer, a Democrat who had his eyes on the presidency after Wilson’s second term.

Hoover and Palmer’s strategy of deporting some of the raids’ leading targets ran into an unanticipated roadblock in the person Louis Post who, as Acting Secretary of Labor, had the final say on deportation. Unintimidated by Hoover and Palmer, Post was “one of the most courageous figures of this grim time,” Hochschild writes. He took the unfashionable position that any non-citizen subject to deportation was entitled to constitutional safeguards. Of approximately 2,500 cases for deportation forwarded to him, Post approved of fewer than 20%, throwing out the majority and asking for further investigation of the remainder.

The renowned radical Emma Goldman presented Post with his highest-profile case. A “larger-than-life celebrity with a fierce gaze and fiery energy,” Goldman had founded an organization to challenge the Selective Service Act which required all men between 21 and 45 to register for military service. By then, Goldman had arguably “enraged the country’s establishment more than any other American of her time.” An immigrant from Russia, Goldman had become a US citizen through marriage. When the government found that her husband had lied to gain naturalization, her citizenship fell with it, making her a deportation target for Palmer and Hoover. But Post applied to Goldman’s case his conviction that no one should be expelled from the United States for opinion alone, thereby thwarting Palmer and Hoover.

But Post could not save Goldman from prosecution under the Espionage Act, and she was charged with espionage on the day the act went into effect. At trial, the prosecutor argued that the danger which she posed arose from her extraordinary oratorical power, capable of holding spellbound “the minds of ignorant, weaker and emotional people.” Goldman thus spent most of the war years in jail, and once the war ended, Hoover moved again for Goldman’s deportation. With Post no longer in office, Goldman was sent back to her native Russia.

No other category of victims experienced what Hochschild aptly terms the “sadistic fury” to which African Americans continued to be exposed during era of the First World War. Racial segregation and overt discrimination were the norm throughout the country in 1917, along with the unrelenting practice of lynching in some regions. Many unions barred African Americans from membership altogether, and even the more egalitarian Wobblies failed to attract many Black members. President Wilson, a Southerner with sympathy for the Confederate cause and views of Black Americans fully in line with the deep-seated racism of the time, had incrementally resegregated the federal workforce. Openly racist politicians were in power throughout the American South.

Despite this dispiriting environment, most Black organizations “did not oppose the war, and encouraged young men to serve.” Even the militant philosopher and journalist W.E. B. DuBois, who became a special target of Hoover, urged his readers to “close ranks” with white Americans in the fight against Germany. DuBois fervently hoped that “if Black soldiers fought bravely, the country would treat them more fairly once the war was over.” This proved to be a forlorn hope, with the era witnessing numerous outbreaks of organized violence against entire African American communities.

A deadly riot took place in East St. Louis, Illinois on July 1, 1917, less than three months after official US entry into the war. After a crowd of angry whites invaded a Black neighborhood and opened fire, Black men responded, killing two whites who turned out to be plainclothes policemen. It was the most severe in decades but hardly the last. Competition for a limited number of jobs in urban centers after the war gave rise to a wave of anti-black violence in many cities during the Red Scare of 1919. In 1921, the year Wilson left office, the now infamous riot in Tulsa, Oklahoma took place, when white mobs effectively wiped out the city’s African American community, looting Black homes and businesses and setting scores of buildings on fire. These outbreaks of violence, almost always described in the press as race riots, should in Hochschild’s view be termed “white riots.” Not surprisingly, President Wilson remained largely silent on the era’s pervasive anti-Black discrimination and violence.

Throughout American Midnight, Hochschild cites repeated instances where Wilson entertained reservations about some of the assaults on civil liberties which his administration had undertaken or acquiesced to, yet failed to take action. Just before leaving for Europe in early 1919 to sell his vision of lasting peace to the United States’ allies, for example, Wilson wrote to Postmaster Burleson suggesting that the time to curtail censorship might have come. But it was not an order. He did not follow up while abroad and Burleson simply ignored the president’s message.

Much of the latter part of American Midnight concern Wilson’s trip to Europe, where he was able to convince his skeptical British and French Allies to include his cherished notion of a League of Nations within the peace treaty they adopted, his failing health due to a series of strokes suffered during and after his time in Europe, which came close to incapacitating him, and his unsuccessful efforts upon his return to convince the United States Senate and the American public of the virtues of a League of Nations. When the isolationist Senate refused to ratify the peace treaty he had negotiated in Europe in November 1919, Wilson’s own isolation was complete, leaving him in the “deepest despair.” It “never seems to have occurred to Wilson,” Hochschild observes, that the “censorship, political imprisonments, and harsh crackdown on antiwar dissidents he had presided over for nearly two years had not nurtured a climate of enthusiasm for a peace-oriented, internationalist ideal like the league.”

The 1920 presidential election constituted a major rebuke to Wilson’s party, when Republican Senator Warren Harding, running on the slogan that it was time to return to normalcy, easily defeated Democratic nominee James Cox (Cox’s running mate was the young Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin Roosevelt). But there was a third candidate on the ballot, charismatic Socialist Party leader Eugene V. Debs, “America’s most beloved leftist,” who received nearly one million votes, 3.4% of the overall total, even though he was then in jail, serving a 10-year sentence after conviction under the Espionage Act for his outspoken opposition to the war (although he had been careful not to advocate avoiding the draft).

Debs, a founder of the Wobblies, had broken with the organization at the outbreak of the First World War. He ran as the Socialist Party candidate for president in 1908 and 1912 but refrained from running in 1916 out of respect for the Wilson campaign’s pledge to keep the United States out of war. Wilson refused to commute Debs’ sentence after the war ended despite considerable pressure to do so. That task fell to Harding, who first met with Debs at the White House, found him surprisingly likeable, and released him, suspending the remainder of his term.

Although generally given low marks in American history books, Harding “undid much of the harsh repression still in place from the war years and the Red Scare,” Hochschild concludes. He moved slowly to free most of the nation’s federal political prisoners: those remaining were freed by his successor, Calvin Coolidge, and all were out of prison by June 1924. “For the first time in seven years, no American was in federal prison because of something he or she had written, said, or believed.”

But did the extreme repression that the country endured between 1917 and 1921 really end after Wilson left office? Hochschild’s answer is a qualified yes. The very excesses of the period gave Americans:

a greater appreciation for the Bill of Rights, something gradually reflected over later decades in school curricula, Supreme Court decisions, and much more. No political mass arrests on the scale of the Palmer Raids happened again […] Never would the government censor news media and put publications out of business the way Albert Burleson had done […] [T]he long battle between business and organized labor rarely again would become as violent as it was more than a century ago.

But Hochschild cites numerous examples of instances where the forces that blighted the United States during the era of the First World War have resurfaced, most recently during the presidency of Donald Trump – exactly 100 years after the second Wilson term – when “rage against immigrants and refugees, racism, Red-baiting, fear of subversive ideas in schools, and much more” once again became “dramatically visible.”

For the United States to avoid slipping back into the darkness that befell the country from 1917 to 1921 requires much from its citizenry, Hochschild advises, pleading above all for precisely what was then missing: a “vigilant respect for civil rights and constitutional safeguards.” With another Trump presidency looming on the political horizon, today’s United States stands perilously close to slipping back into a darkness reminiscent of that which Hochschild describes so vividly in this chilling yet instructive volume.

Image credit: American Midnight: The Great War, a violent peace, and democracy’s forgotten crisis [Cover] (Harper Collins), Fair Use.