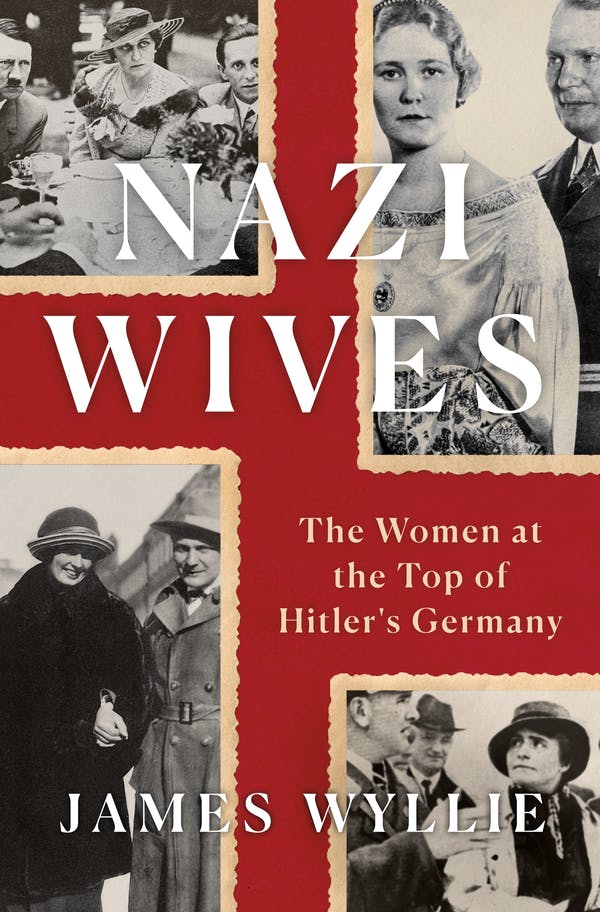

“Nazi Wives: The Women at the Top of Hitler’s Germany”

A book review of James Wyllie’s Nazi Wives: The Women at the Top of Hitler’s Germany (St Martin’s Press, 2019).

Within the proliferation of literature on seemingly every aspect of Adolph Hitler’s Nazi regime, women have hardly been overlooked.[1] But according to freelance British journalist and screenwriter James Wyllie, there has never been an in-depth study of the wives of the most notorious Nazis. He seeks to fill this gap in Nazi Wives: The Women at the Top of Hitler’s Germany. The absence of a serious study of the top Nazi wives, Wyllie contends, bolsters the claim made after World War II that they were helpless bystanders as the Nazi terror unfolded, an argument he seeks to refute. A close look at the women who married the leading Nazis also yields important insights into the nature of Nazi rule and the psychology of its leaders, he argues.

In Nazi Germany, women were above all expected to be child bearers, adding to the stock of the master race, while remaining compliant and subservient to their husbands. The ideal Nazi woman, although supportive of the goals and aspirations of the Third Reich, was to be largely apolitical, with the serious questions of politics reserved for the men. Concentrating on six women, Wyllie aims to demonstrate how the wives of the Nazi leaders adhered in varying degrees to these standards, while also using their positions near the top of the party hierarchy to involve themselves, directly or indirectly, in the Nazi project.

The women Wyllie profiles include Isle Hess, wife of Rudolf Hess, who was Hitler’s chief deputy until he flew a solo mission to Scotland in 1941 in an attempt to negotiate peace with Great Britain; Magda Goebbels, married to chief Nazi propagandist Joseph Goebbels; Margaret Himmler, wife of Heinrich Himmler, head of the Schutzsaffell, the SS, the German paramilitary security unit, and a chief architect and implementer of the Holocaust; Gerda Bormann, whose husband Martin served as Hitler’s private secretary; Emmy Goering, second wife of Hermann Goering, commander-in-chief of the German Air Force, the Lutwaffe; and Lina Heydrich, married to Reinhard Heydrich, Himmler’s chief deputy in the SS who shared responsibility for design and implementation of the Holocaust and served as administrator of annexed Czechoslovakia until assassinated in Prague in 1942. Also featured are Goering’s Swedish first wife Carin, perhaps the most fanatical Nazi among the women depicted in the book, who died early in her husband’s career; and Eva Braun, Hitler’s mistress who became his wife 36 hours before both took their own lives in a Berlin bunker as the Red Army moved in on the shattered capital.

Wyllie has amassed an impressive amount of information about these women, arranged in rough chronological order against the backdrop of familiar events, beginning with the Nazis’ rise from obscurity to power in the post-World War I period, through their defeat in 1945, and ending in the early post-World War II era. He goes into strikingly intimate detail: how they met their husbands, in some cases when the couple first had sex, how their marriages functioned and malfunctioned, how they squabbled among themselves, and the children each couple reared.

The six women came from similar backgrounds. All were reasonably well educated, raised in conservative middle-class families, of either Catholic or Protestant confession. They were inculcated with what Wyllie describes as a sense of “strident patriotism” based on a belief in the superiority of German culture, a hatred of socialism and a “fear that the unruly masses would devour them.” They came of age in the “profoundly insecure and volatile circumstances” of post-World War I Germany. “Old certainties were gone,” writes Wyllie. “The civilized conventions of their parents’ generation appeared increasingly irrelevant. Cut adrift, they each gravitated towards a self-styled savior who promised the world.”

That savior was of course Adolph Hitler, the Führer. Even in a study of women, Hitler is unavoidably the book’s core character. Each of the women Wyllie portrays had a different relationship to the Führer, but all were able to “enjoy their many privileges and their gilded lifestyles because Hitler allowed them to.” Consequently, the book probes each woman’s relationship to the ominous head of the Third Reich. “Any power the top Nazi wives had was entirely dependent on his goodwill,” Wyllie asserts. “One false move was enough to ruin them; Hitler could reduce them to nothing with the wave of his hand.”

But Wyllie also probes the women’s relationship to the Nazi regime broadly conceived, examining their ideological side, their anti-Semitism, and the degree to which they were aware of the gruesome details of the Nazi project. After the Nazi defeat, none who survived the war evinced any willingness to accept responsibility for the havoc and destruction their husbands had wreaked upon Germany and Europe. But these weighty questions are relegated mostly to the final chapters and seem secondary to the mundane and sometimes prurient details of the women’s personal lives.

Hitler’s Extended Family

Hitler abstained from marriage and a normal family life because he considered himself married to the German people; he consequently kept his relationship with Eva Braun under wraps and largely out of public view (For more on Braun, see my 2013 review of two biographies on her life). When off-duty, the Führer preferred the company of women and took great interest in the top Nazi wives, a gesture “bound up with his need for an extended family.” He was “more relaxed and comfortable in the company of women, as long as they openly and unconditionally adored him, didn’t discuss politics and conformed to the stereotypes he found attractive,” Wyllie writes. When necessary, the Führer played the role of matchmaker and marriage counselor for his extended family.

Hitler coaxed Deputy Führer Rudolph Hess into popping the question with an impatient Isle Pröhl. Isle had been involved with the procrastinating Hess for more than seven years, in a relationship Wyllie describes as sexless, held together primarily by the couple’s “unquestioning enthusiasm for Hitler’s poisonous ideology.” The couple married in a small civil ceremony in December 1927, with Hitler serving as a witness.

The Führer took a different route to coax Magda Quant into marriage with his chief propagandist, Joseph Goebbels. Magda, “sophisticated, multilingual, well-travelled, elegant, poised, at ease in elevated company and never short of male admirers,” had been married and was divorced when she first met Joseph while working in his propaganda department. From the beginning it was a volatile relationship, in no small measure because Joseph rejected monogamy as an “outdated bourgeois convention” and “made no secret of his own insatiable sexual appetite,” though he could not abide the thought of Magda with another man.

Hitler fantasized about having a clandestine affair with Magda and concluded that might be enhanced if she were married. Magda, no doubt infatuated with the Führer, appeared willing to enter a triangular relationship that would involve marrying the chief Nazi propagandist. We don’t learn whether Hitler’s interest in Magda ever progressed beyond fantasy, but Magda and Joseph married in 1931, with Hitler again serving as a witness.

When Joseph’s affair with a Czech actress took the couple to the cusp of divorce, the Führer intervened, bringing them together at his mountain retreat, the Berghof, where he made “brutally clear” that they would have to mend their marriage and Joseph would have to stop seeing his Czech paramour; otherwise, both would lose their exalted places in the Nazi hierarchy. The couple got the message and stayed together. Altogether, their marriage produced six children, all of whom they infamously killed before they committed suicide in the final days of the Third Reich.

Magda Goebbels appears to have been the only one of the six Nazi wives who did not genuinely love and admire her husband. But she was hardly the only one whose marriage was tested by her husband’s extramarital affairs. Margaret Boden, a Red Cross nurse, married SS chief Heinrich Himmler, eight years younger. After having a daughter and adopting a son together, her dour husband fell in love with his twenty-six-year-old secretary, Hedwig. She and the SS chief had two children together. Although Heinrich spent most of his spare time with Hedwig and his new family, he regularly wrote tender love letters to Margaret and delivered presents to her and their children. At Christmas 1944, with the Nazi war machine in full retreat, Margaret expressed in her diary how proud she was that “all of Germany” looked up to her husband.

Gerda Buch, daughter of Walter Buch, a high-ranking military officer in World War I who fell under Hitler’s spell in the aftermath of the war, met Hitler when she was a teenager and called him “Uncle Adolf.” From an early age, Gerda “lived and breathed Hitler’s ideology. It was second nature to her.” Through her father, Gerda met Martin Borman, who surely calculated that an “association with the daughter of such a prominent Nazi could only smooth his passage through the ranks of the party.” When the couple wed, Hitler and Hess served as witnesses.

Gerda, whom Wyllie depicts as the wife most closely adhering to ideal Nazi feminine standards, had seven children with Martin, even while her husband pursued liaisons with multiple women during the couple’s married life and probably abused his wife physically. Gerda didn’t fight back, didn’t seek help, and didn’t confide in anyone else. She believed it was her duty to obey her husband. According to Wyllie, there was “every indication that she was truly devoted to Bormann.”

Gerda also befriended Himmler’s mistress Hedwig. That Himmler was married didn’t bother her; it was the natural way men were, the “healthy expression of a man’s biological need to reproduce.” She had the same attitude toward her husband and his serial extra-marital affairs. When Martin departed from his usual habit of short stands by falling for an actress—one who had previously rejected Goebbels’ advances—Gerda was oddly unopposed to the affair. She seems to have conceived of a ménage-à-trois where the two women would produce children for Martin, thereby contributing to Germany’s efforts to increase its sagging national birthrate.

Family Feuds

The Nazi leadership was notorious for its infighting, bureaucratic rivalries, and palpable pandering for the Führer’s favor. It is thus no surprise that acute competition also marked many of the relationships between the wives of the top leadership. Each of the Nazi wives sought the informal moniker of “First Lady” of Nazi Germany, a contest to which Wyllie returns repeatedly. Eva Braun, although recognized among the women at the Berghof as the Führer’s alter ego, was kept under wraps and never part of the competition (she was nevertheless often quite assertive towards the other women at the Führer’s mountain retreat). Once the Nazis seized power in 1933, Magda Goebbels was the obvious candidate to assume this public role. She gave the first Nazi Mother’s Day address via national radio, and was often photographed alongside her husband and their children, portraying an image of the “perfect Nazi family.”

But the Goebbels’ marital difficulties left Magda open to competition from Emmy Goering, Herman’s second wife and an accomplished actress. While all the Nazi wives lived well during the 1930s and most of the war years, the Goerings’s life of unabashed opulence set them in a class by themselves. Their vast estate, known as “Carinhall” after the deceased Carin, dwarfed the accommodations of the other high-ranking Nazis. The couple’s lavish lifestyle attracted significant public attention. For a while during the mid-1930s, Emmy and Herman became the Nazis’ “first couple.”

But if Emmy’s increasingly high profile was a “direct challenge to Magda’s status as the First Lady of the Reich,” Magda was able to hold on to her title because Hitler never warmed to Emmy. Among the top wives, she was the “least interested in Nazism.” Hitler didn’t disparage or criticize her, but he was “never relaxed around her either,” Wyllie indicates. “There was none of the intimacy or the meeting of minds that he experienced with Magda.”

The fiercest rivalry was between Lina Heydrich and Margaret Himmler, whose husbands forged a surprisingly close working relationship as top SS brass until Reinhard Heydrich was assassinated in Prague in 1942, leaving Lina a widow. Before her husband’s death, Lina yearned to be the most influential SS wife, a position Margaret held by virtue of her husband’s lead role in the SS. Lina disdained standing in Margaret’s shadow. She believed Margaret to be “inferior to her in every way and never missed an opportunity to ruthlessly put her down.” She sabotaged Margaret’s efforts to host regular tea parties for SS wives, among other slights. Margaret, less outspoken than Lina, sought to have her husband tell Lina’s husband that he should divorce Lina.

But for all the energy the two women expended swiping at one another, Wyllie describes both as “snobs” who “looked down their noses at most of humanity.” Moreover, the two women shared a fervent anti-Semitism. Margaret, visiting the Eastern Front, reacted to the “Jew trash” she saw by remarking that “most of them don’t even look like human beings.” As a young woman, Lina loathed the Polish Jews who had settled in her Baltic fishing village, whom she viewed “like an alien species.” Later, when she lived on an estate outside Prague, according to one of the estate’s Jewish prisoners, she “spat at her workers, calling them ‘Jewish pig[s].’”

Reckonings

All but Magda Goebbels survived the war and each found herself alone in the post war era. Along with Joseph Goebbels, Himmler and Goering took their own lives, and Bormann likely did the same. Hess remained imprisoned until his death in 1987. The post-war justice system instituted by the Allies treated the women lightly. But all engaged in denial and deception over their roles and those of their husbands in the Nazi project. Margaret Himmler told an American journalist she had seen press coverage about the death camps and “knew her husband would be blamed.” She was “just a woman,” she told the journalist, and “did not understand politics.”

Lina Heydrich wrote a book, candid and in its own way “disarmingly honest.” She was unapologetic about the ideological convictions she shared with her husband, and shameless about their racism, while downplaying her husband’s direct involvement in the Holocaust. Lina was obsessed by the idea that her husband was being treated “unfairly by posterity.” He was being judged harshly for acts he considered an “unavoidable political necessity,” as she put it. It was all too easy to condemn the “decisions of those times from today’s warm bed,” she wrote.

Emmy Goering wrote a spirited a defense of her husband, My Life with Goering, which avoided the issues that had marked her husband’s career. Her husband’s only crime had been loyalty to Hitler, she contended. A woman in love “thinks only of her partner’s success, and it is of little importance to her how he obtains it,” she wrote. Among the top Nazi wives, however, Emmy came closest to expressing an iota of remorse about what the Nazis had done and the extent to which she and her husband may have been responsible.

“I often wonder now,” Emmy wrote, if we should not have been “a little more vigilant and when we saw injustices being done, if we should not have put up stronger resistance, especially to Hitler over the Jewish question.” Wyllie characterizes Emmy’s uneasiness as “willful blindness,” which was “not accidental” but rather “typical of many Germans who benefited from the regime and preferred to ignore its brutal excesses and look the other way, rationalizing their lack of resistance and passive complicity.” In an account heavy on the minutiae of the personal lives of the top Nazi wives, this “willful blindness” may be the most palpable common thread tying those lives together.

[1] A leading work on the topic is Wendy Lower’s Hitler’s Furies: German Women in the Nazi Killing Fields, a nuanced study of women who joined the Nazi cause in surprising numbers and willingly and enthusiastically abetted the Holocaust. My 2016 review of Lower’s work can be found here.

6 Comments