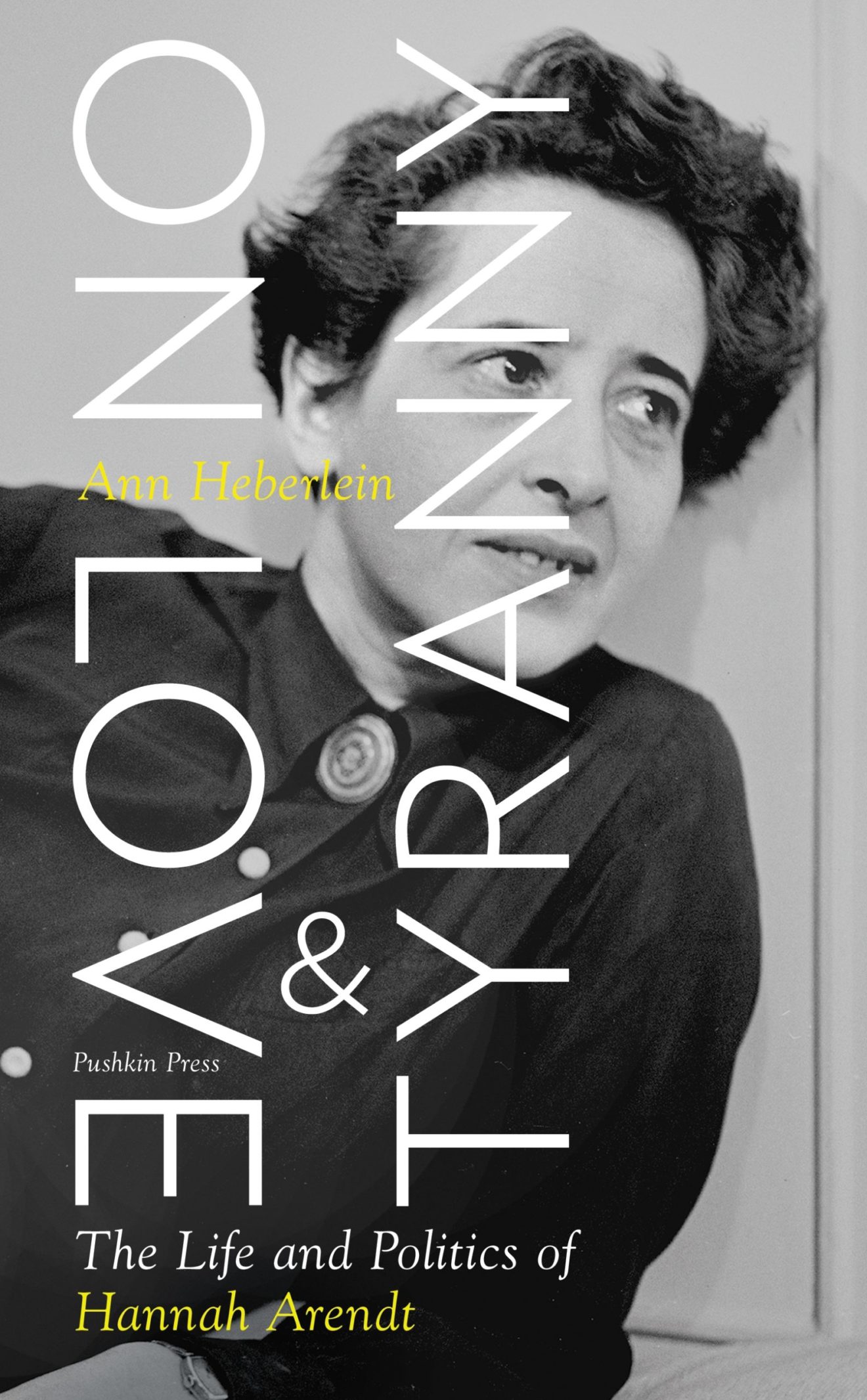

“On Love and Tyranny: The Life and Politics of Hannah Arendt”

A book review of Ann Heberlein’s On Love and Tyranny: The Life and Politics of Hannah Arendt. Translated from Swedish by Alice Menzies (Pushkin Press, 2021).

A book review of Ann Heberlein’s On Love and Tyranny: The Life and Politics of Hannah Arendt. Translated from Swedish by Alice Menzies (Pushkin Press, 2021).

Before she became a celebrated New York public intellectual, Hannah Arendt (1906–1975) lived through some of the twentieth century’s darkest moments. She fled her native Germany after Hitler came to power in 1933, living in France for several years. In 1940, she spent time in two intern camps, then departed for the United States, where she resided for the second half of her life. In 1950, Arendt became an American citizen, ending a period of nearly two decades of statelessness. The following year, she established her reputation as a serious thinker with The Origins of Totalitarianism, a trenchant analysis of how oppressive one-party systems came to rule both Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in the first half of the 20th century. As a commentator observed in The Washington Post, Arendt’s work diagnosed brilliantly the “forms of alienation and dispossession that diminished human dignity, threatened freedom and fueled the rise of authoritarianism.”

The Origins of Totalitarianism was one of a handful of older works that experienced a sudden uptick in sales in early 2017, after Donald Trump became president of the United States (George Orwell’s 1984 was another). The authoritarian impulses that Arendt explained and that Trump personified seem likely to continue for the foreseeable future, both in the United States and other corners of the world. For that reason alone, a fresh look at Arendt is welcome. Such a contribution has now been provided by Ann Heberlein, a Swedish novelist and non-fiction writer, with her recent On Love and Tyranny: The Life and Politics of Hannah Arendt.

Heberlein’s work, ably translated from the original Swedish by Alice Menzies, constitutes the first major Arendt biography since 1982, when Elisabeth Young-Bruehl’s highly-acclaimed but dense Hannah Arendt: For Love of the World first appeared. On Love and Tyranny, by contrast, is easy to read yet hits all the highlights of Arendt’s life and work. Disappointingly, there are no footnotes and little in the way of bibliography. Heberlein makes use of the diaries of a key if problematic figure in Arendt’s life, philosopher Martin Heidegger, which only became public in 2014, and are best-known for casting additional light on Heidegger’s Nazi sympathies. But it is difficult to ascertain from the book itself what other new or different sources Heberlein utilized that might have been unavailable to Young-Bruehl.

Although Arendt studied philosophy as a university student, she preferred to describe herself as a political theorist. But despite the reference to politics in her title, Heberlein’s portrait accents Arendt’s philosophic side. She emphasizes how the turbulent circumstances that shaped Arendt’s life forced her to apply in the real world many of the abstract philosophical and moral concepts that she had wrestled with in the classroom. As the title suggests, love and tyranny feature prominently among them, but others include good versus evil, or truth, obligation, responsibility, forgiveness, and reconciliation.

At Marburg University, where she entered in 1924 as an eighteen-year-old first year student, Arendt not only studied philosophy under Heidegger, already a rising star in German academic circles, but also began a passionate love affair with the man. Heidegger was then nearly twice her age and married with two young sons (their affair is detailed in Daniel Maier-Katkin’s astute Stranger from Abroad, Hannah Arendt, Martin Heidegger: Friendship and Forgiveness, reviewed on my personal blog in 2013).

Arendt left Heidegger behind when she fled Germany in 1933, but after World War II re-established contact with her former teacher, by then disgraced because of his association with the Nazi regime. A major portion of Heberlein’s work scrutinizes Arendt’s subsequent, post-war relationship with Heidegger.

Heberlein also zeroes in on Arendt’s very different post-war relationship to a seemingly very different man, Adolph Eichmann, Hitler’s loyal apparatchik who was responsible for moving approximately 1.5 million Jews to Nazi death camps. Arendt’s series of articles for The New Yorker on Eichmann’s trial in Jerusalem in 1961 became the basis for another of her best-known works, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, published in 1963, in which she portrayed Eichmann as neither a fanatic nor a pathological killer, but rather a stunningly mediocre individual, motivated more by professional ambition than by ideology.

The phrase “banality of evil,” now commonplace thanks to Arendt, followed her for the rest of her days. How the phrase applies to Eichmann is of course well-ploughed ground, to which Heberlein adds a few insights. Less obviously, Heberlein lays the groundwork to apply the phrase to Heidegger. Her analysis of the banality of evil suggests that the differences between Heidegger and Eichmann were less glaring in the totalitarian Nazi environment, where whole populations risked losing their ability to distinguish between right and wrong.

Arendt was the only child of Paul and Martha Arendt, German Jews who were prosperous, progressive, and secular. Paul died when Hannah (born Johanna) was seven, but she remained close to her mother, who immigrated with her to the United States in 1941. Meeting with Heidegger as a first-year student in 1924 was for Arendt “synonymous with her entry into the world of philosophy,” Heberlein writes. Heidegger was “The Philosopher personified: brilliant, handsome, poetic, and simply dressed.” The Philosopher made clear to the first-year student that he was not prepared to leave his wife and family or the respectability of his academic position for her. She met him whenever he had time and was able to escape his wife.

The unbalanced Arendt-Heidegger relationship “existed solely in the shadows: never acknowledged, never visible”, as Heberlein puts it. Arendt was never able to call Heidegger her partner because she “possessed him for brief intervals only, and the fear of losing him was ever-present.” Borrowing a perspective Heberlein attributes to Kierkegaard and Goethe, she describes Arendt’s love for Heidegger as oscillating “between great joy and deep sorrow—though mostly sorrow.” For these writers, whom Arendt knew well, love consisted “largely of suffering, of longing, and of distance.” The eighteen-year-old, Heberlein concludes, was “struck down by a passion, possibly even an obsession, that would never fade.”

Arendt left Marburg after one year, ending up at Heidelberg University. She later admitted that she needed to get away from Heidegger. But she continued to see him while she wrote her dissertation at Heidelberg on St. Augustine’s conception of love. Her advisor there was the esteemed theologian and philosopher Karl Jaspers, with whom she remained friends up to his death in 1969.

After university, Arendt worked in Berlin, where she met Gunther Stern, a journalist, poet and former Heidegger student who was closely associated with the communist Berthold Brecht. Arendt married Stern in 1929 at age twenty-three. Sometime during her period in Berlin, she cut off all contact with Heidegger. But after the Nazis came to power, Arendt began hearing alarming rumors about several specific anti-Semitic actions attributed to Heidegger at Fribourg University, where he had been appointed rector. She asked him in a letter to clarify by responding to the rumors, and received back a self-pitying, aggressive response that she found entirely unconvincing.

1933 was also the year Arendt and her mother left Germany and wound up in Paris. There she met Heinrich Blücher, a self-taught, left-wing German Jewish political activist. She and Stern had by then been living apart for several years, and she divorced him to marry Blücher in early 1940. The couple remained together until Blücher’s death in 1970. They were sent to separate intern camps just prior to the fall of France in 1940, but escaped together through Spain to Portugal, where they immigrated to the United States in 1941 and settled in New York.

Arendt’s first return trip to Europe came in late 1949 and early 1950. With Blücher’s approval, she sought out her former teacher, then in Fribourg, meeting with Heidegger and his wife Elfried in February 1950. Although understandably suspicious of Arendt, Elfried seems to have understood that Arendt was in a position to help rehabilitate her husband, besmirched by his association with the Nazi regime. She thus accepted that he wanted Arendt to again be part of his life. Arendt maintained a warm relationship with her former professor until her death in 1975 (Heidegger died less than a year later), writing regularly and meeting on several occasions.

In the post-war years, as Arendt’s star was rising, she became Heidegger’s unpaid agent, working to have his writings translated into English and negotiating contracts on his behalf. She also became an enthusiastic Heidegger defender, going to great lengths to excuse, smooth over, and downplay his association with Nazism. She once compared Heidegger to Thales, the ancient Greek philosopher who was so busy gazing at the stars that he failed to notice that he had fallen into a well.

On the occasion of Heidegger’s eightieth birthday in 1969, she delivered an over-the-top tribute to her former professor. She reduced Heidegger’s dalliances with Nazism to a “10-month error,” which in her view he corrected quickly enough, “more quickly and more radically than many of those who later sat in judgment over him.” Arendt argued that Heidegger had taken “considerably greater risks than were usual in German literary and university life during that period.” As Heberlein points out, Arendt’s tribute was a counter-factual fantasy: there was no empirical support for this whitewashed version of the man.

Heidegger had openly endorsed Nazi “restructuring” of universities to exclude Jews when he became rector at Fribourg in 1933 and his party membership was well known. His diaries, published in 2014, made clear that he was aware of the Holocaust, believed it was at least partly the Jews’ fault and, even though he ceased to be active in party affairs sometime in the mid-1930s, remained until 1945 a “fully paid-up, devoted supporter of Adolph Hitler.” Arendt of course didn’t have access to these diaries when she rose to Heidegger’s defense, but it seems unlikely they would have changed her perspective.

Arendt’s 1969 tribute left little doubt she had found her way to forgive Heidegger for his association and support for a regime that had murdered millions of her fellow Jews, wreaked destruction on much of Europe, and forced her to flee her native country to start her life anew an ocean away. But why? Heberlein writes that forgiveness for Arendt was the conjunction of the conflicting powers of love and evil. “Without evil, without betrayal, insults and lies, forgiveness would be unnecessary; without love, forgiveness would be impossible.” Arendt found the strength to forgive Heidegger in the “utterly irrational emotion” that was love. Her love for Heidegger was “strong, overwhelming, and desperate. The power of the passion Hannah felt for Martin was stronger than the sorrow she felt at his betrayal.” But whether it was right or wrong for her to forgive Heidegger, Heberlein demurely concludes, is a question only Arendt could have answered.

Did Arendt also forgive Eichmann for his direct role in transporting a staggering number of Jews to death camps? Is forgiveness wrapped within the notion of the banality of evil? Daniel Maier-Katkin suggests in his study of the Arendt-Heidegger relationship that in her experience with Heidegger, Arendt may have come to the notion of the banality of evil “intuitively and without clear articulation.” That experience may have prepared her to comprehend that each man had been “transformed by the total moral collapse of society into an unthinking cog in the machinery of totalitarianism.”

Heberlein’s analysis of Eichmann leads to the conclusion that the notion of the banality of evil was sufficiently elastic to embrace Heidegger. Heberlein sees the influence of Kant’s theory of “radical evil” in Arendt’s notion of the banality of evil. For Arendt, as for Kant, evil is a form of temptation, in which the desires of individuals overrule their “duty to listen to, and act in accordance with, goodwill.” The antidote to evil is not goodness but reflection and responsibility. Evil grows when people “cease to think, reflect, and choose between good and evil, between taking part or resisting.” Arendt’s sense of evil recognizes an uncomfortable truth that seems as applicable to Heidegger as to Eichmann, that most people have a tendency to:

follow the path of least resistance, to ignore their conscience and do what everyone else is doing. As the exclusion, persecution, and ultimately, annihilation of Jews became normalized, there were few who protested, who stood up for their own principles.

For Arendt, forgiveness of such persons is possible. But not all evil can be explained in terms of obedience, ignorance, or neglect. There is such a thing as evil that is “as incomprehensible as it is unforgiveable.” In Heberlein’s interpretation of Arendt, the genuinely evil person is the one who is “leading the way, someone initiating the evil, someone creating the context, ideology, or prejudices necessary for the obedient masses to blindly adopt.” Whether Eichmann falls outside this standard for genuine evil is debatable. But the standard could comfortably exclude Heidegger, as Arendt had in effect argued in her 1969 tribute to her former teacher.

Arendt compounded her difficulties with the separate argument in Eichmann in Jerusalem that the Jewish councils that the Nazis established in occupied countries cooperated in their own annihilation. The “majority of Jews inevitably found themselves confronted with two enemies—the Nazi authorities and the Jewish authorities,” Arendt wrote. The “pathetic and sordid” behavior of Jewish governing councils was for Arendt the “darkest chapter” of the Holocaust—darker than the mass shootings and gas chambers—because it “showed how the Germans could turn victim against victim.”

The notion that Arendt was blaming the Jews for their persecution “quickly took hold,” Heberlein writes, and she was “forced to put up with questions about why she thought the Jews were responsible for their own deaths, in virtually every interview until she herself died.” After Eichmann in Jerusalem, Arendt was shunned by many former colleagues and friends, repeatedly accused of being an anti-Israel, self-hating Jew, “heartless and devoid of empathy . . . cold and indifferent.” When her husband died in 1970, Arendt’s isolation only increased. Her ongoing exile, this time existential, surely enhanced her emotional attachment to Heidegger, the sole remaining link to the world of her youth.

Arendt’s ardent post-war defense of Heidegger, while generating little of the brouhaha that surrounded Eichmann in Jerusalem, is also a critical if puzzling piece in understanding her legacy. Should we consider the continuation of her relationship with Heidegger as the simple but powerful triumph of Eros, an enduring schoolgirl crush that even the horrors of Nazism and the Holocaust were unable to dispel? Heberlein’s earnest biography points us inescapably in this direction.

1 Comment